- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Politics

by Robert Schlesinger

He's got a great fastball, but he needs other pitches

Mariano Rivera is the greatest closer in baseball history. For a dozen years, baseball fans have known that his arrival in a close ballgame virtually guarantees a

What makes Rivera's dominance more astounding is the fact that his repertoire consists of a single pitch, the cut fastball.

Presidents are like pitchers. Success requires doing several things well; they cannot rely on one political skill. Their effectiveness is ultimately a function of their ability to exercise all elements of presidential power.

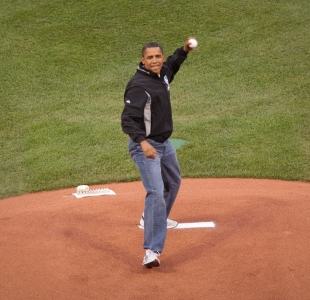

Which brings us to Barack Obama, who might be as near as professional politics has to a Mariano Rivera. Obama has ridden a single pitch--speechmaking--to the pinnacle of politics. He spoke his way to the

But while Obama and his team understand the power of presidential rhetoric, nagging questions remain about whether they understand its limits.

To be sure, it is hard to understate the importance of the "bully pulpit." The two most effective modern presidents were also the two most eloquent--Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan. And even our less eloquent chief executives are often remembered for how their special moments of oratorical brilliance galvanized a nation (Lyndon Johnson promising that "we shall overcome") or educated the people (Dwight Eisenhower's warning about "the military-industrial complex").

And the leaders who never grasped the importance of that aspect of presidential power did not last long in office. Think of George H.W. Bush (most remembered for a phrase, "Read my lips," which he uttered before becoming president), Jimmy Carter (most remembered for a word, malaise, he did not say in the so-called malaise speech), and Gerald Ford.

But the presidents who best understood the power of words also understood their limits. The

FDR redefined the rules of presidential communication in ways that linger today. One important rule for the president and his team: Beware overexposure lest you squander presidential power. Warnings abounded of Obama fatigue as early as the spring, but

Even if that is true, presidents must skillfully use more than one aspect of presidential power. For a speech to be effective, the broader political context has to be receptive to the message. But if anything, Obama's legislative strategy has undercut his great strength. On healthcare, he has laid out broad principles but, before last week's address, let others fill in the details. This approach bespeaks the leadership of a

And there are signs that overexposure and a legislative approach incompatible with his rhetorical strengths are hampering Obama. He reportedly has given more than two dozen speeches and statements on healthcare since the start of June, even as his approval rating has dropped from an average of over 60 percent, according to Real Clear Politics' composite of polls, to just below 53 percent. And while his first prime-time press conference in February drew 50 million viewers, his most recent one, in July, drew only half that.

At the same time, according to pollster.com, Obama's average healthcare approval rating has gone from 50 to 40 percent in favor to 50 to 40 against.

Obama had his good fastball when he spoke to

That's the route not only to a victory in this debate but to a winning season for Team Obama.

AMERICAN POLITICS

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Receive our political analysis by email by subscribing here

Speeches Not Enough for Obama to Succeed

© Tribune Media Services, Inc