- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Politics

by Katherine Skiba

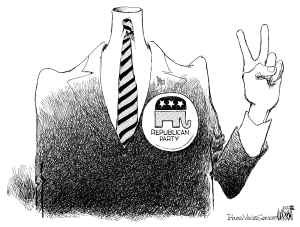

Editorial Cartoon by Don Wright

In the Senate, Two Is a Lonely Number. The dwindling Republican moderates have real worries about the future of the GOP

When Maine's two U.S. senators, Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins, broke ranks with all but one other Republican and voted "Yes" on President Barack Obama's $787 billion stimulus, they handed the White House an early, critical win.

As some Republicans seethed, the two were celebrated as the most powerful women in Washington.

The only Republican senator to join Snowe and Collins in voting for the stimulus bill vote was Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania.

Democrats needed at least two of the three votes for the bill to reach Obama's desk.

Weeks later, Specter, a moderate who had long been courted by Democrats, abandoned the GOP, his home for 43 years, in an about-face that was both stunning and predictable: stunning because he had often insisted that he would never flee his party, and predictable because in doing so he joined a long list of moderate Republican senators who are yesterday's news.

The Senate once was a comfortable home for GOP centrists, with household names like John Warner of Virginia, Alan Simpson of Wyoming, John and Lincoln Chafee of Rhode Island, and three Oregonians: Bob Packwood, Mark Hatfield, and Gordon Smith.

Another moderate, Jim Jeffords of Vermont, famously defected from the GOP in 2001 and restyled himself an independent.

Jeffords declined to run again in 2006. Snowe felt the 2006 losses personally; she carried Maine handily with 74 percent of the vote, but two neighbors in the Senate's Russell Building went down, Mike DeWine of Ohio and Lincoln Chafee. And when Oregon voters threw Smith out in 2008, the three states on America's "Left Coast" lost the only GOP senator they had.

"It's devastating, really, when you look at the totality of the picture and the imbalance it has created in our party," Snowe says. "Somebody wrote to me recently and said, 'If Republicans don't watch out, we'll have the smallest tent in history for a political party.'"

The stimulus vote demonstrated the clout Collins and Snowe wield with Democrats short of the 60 votes needed to advance controversial bills. But their outsize influence has done nothing to tamp down their real worries about the future of the Grand Old Party.

A pivotal figure in negotiations on the stimulus, Collins was bombarded with about 100,000 E-mails in the days leading up to the vote: about 13,000 from Mainers, who were split on the issue, and the rest from mostly angry out-of-staters who condemned her "in very personal terms," Collins says.

National politics can be as much a contact sport as ice hockey, something Mainers know a thing or two about. But what's curious about the anti-Collins campaign is who she thinks was behind it. Though she won't name him publicly, she blames a fellow GOP senator for unleashing it.

It used to be that the Republican Senate caucus, which has shrunk to 40 lawmakers, was much more collegial. But while she is "disappointed" by the sharp elbows, Collins worries more about the broader implications of the dwindling number of GOP centrists. And her concern is echoed by Snowe. They say the loss of moderates is bad for the GOP, bad for their region, and bad for America. And they fear that the party ultimately could cede turf to moderate Democrats, jeopardizing hopes of regaining congressional majorities and putting the GOP at risk in future presidential contests.

Collins coasted to re-election last fall with 61 percent of the vote, but throughout the six states of New England (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut) she saw a distressing pattern.

With four Senate battles and 22 House races across the region, "I was the lone victor" among GOP hopefuls, she says. In the House, no Republican anywhere on the ideological spectrum now represents New England, once a GOP stronghold.

Collins believes that as party allegiances become more entrenched in many places, the competition between parties is dropping off and debate is being stifled.

And this, she says, isn't good for the GOP's prospects: "We're not going to win presidential elections if we become increasingly a party of white, Southern men."

Toe the GOP line

The new chair of the Republican National Committee, former Maryland Lt. Gov. Michael Steele, is an African-American whose choice was intended to prevent that. But he found himself in hot water with the Senate centrists when he threatened to fund primary challengers against them if they didn't toe the line on key votes.

"Strange," says Collins.

"Horrendous," says Snowe. "I have been in Congress for 30 years, and there was always sort of an understanding that, obviously, senators and members of the House are going to depart from the norm of the Republican Party" on some votes. "You're reflecting the views of your constituents," she says.

Look across America, and you'll understand their alarm.

The GOP's advantage in party affiliation among voters peaked in 2003. One recent poll found that 53 percent of Americans are Democratic or Democratic leaners; only 35 percent fell in the Republican camp. Other polls have found that by a big margin, people think congressional Democrats care more about average people than do their GOP counterparts.

Gary Jacobson, a political scientist at the University of California-San Diego, says what's most disturbing to Republicans is that Obama carried 66 percent of voters under 30. That's a bad omen for the GOP.

If you ask Americans where they reside on the ideological spectrum, most point to the center.

In last fall's presidential exit polls, 44 percent described themselves as "moderate," compared with 34 percent who said "conservative" and 22 percent who answered "liberal."

But while most people are centrists, for years the national parties have come under the grip of people on the extreme edges.

Specter, in leaving the GOP, identified two contests to make that point. One was the defeat of Democrat Joe Lieberman of Connecticut in a 2006 primary contest against liberal challenger Ned Lamont; Lieberman prevailed in the general election as an independent. The other race was Specter's challenge from the right by former House member Pat Toomey, who nearly toppled him in a 2004 primary. Toomey, former president of the anti-tax Club for Growth, has launched another campaign to oust Specter in 2010.

Collins is warily eyeing the Senate Democratic caucus, where centrists are coalescing to flex their muscle. Sixteen lawmakers, led by Democrats Evan Bayh of Indiana, Tom Carper of Delaware, and Blanche Lincoln of Arkansas, have formed a moderate working group. Collins says its members are Democrats who have carried Republican-leaning states. "If we don't run moderate Republicans who fit these states," she cautions, "we're going to end up with conservative or moderate Democrats representing them."

Republican Party Evolution

Over time, parties evolve, expand, and contract, some to the point of extinction.

Scholars say the demise of moderate Republicans in the Senate has been occurring since the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which triggered defections among Southern Democrats. "You no longer had a Democratic Party in Congress that was roughly one-half Southern conservative and one-half Northern liberal," says Norman Ornstein, a congressional scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. But with many watching as the South morphed from Democratic to competitive to Republican, less attention was paid to the Republicans dropping off in the Northeast and the West Coast.

Though regions have shifted over time, ideological views are hardening. Ross Baker, a political scientist at Rutgers, looks not only at elected GOP officials but also at their growing "supporting casts" in the world of talk radio, think tanks, opinion journals, and blogs. "Back in the 1940s, it was hard to identify anything like a Republican think tank," he says.

Snowe and Collins, the highest-profile GOP moderates left, insist Obama can't always count on their vote. Neither approved the Democratic budget outline, for example, and both oppose a pro-union measure known as "card check." And each has turned aside pressure by Democrats to leave the GOP. Snowe says there have been several major overtures over the years. "A lot of Democrats will kid me. They'll say, 'Oh, Olympia, you really should be a Democrat.' I tell them I couldn't do it. This is my identity."

Collins agrees. "I would never switch parties," she says. "My DNA is moderate Republican

With few moderates left in the Senate to bridge a widening chasm, Baker says, it may be that most Senate Republicans are hoping, as conservative talk king Rush Limbaugh exclaimed, that Obama fails.

"Although they may dispute the bluntness with which Limbaugh expressed it, I think they probably would agree that their best chance is that Barack Obama falls flat on his face -- that credit remains tight, that housing starts remain low, that the market sags," Baker says.

Democratic Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts, gloating after Specter's big switch, said the exit showed that the GOP is a place "where moderates need not apply."

Snowe and Collins would take issue with him on that point but might agree on this one:

For all their power, there's no mistaking that two is a lonely number.

AMERICAN POLITICS

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Receive our political analysis by email by subscribing here

© Tribune Media Services