- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Economy

by Kim Clark

Communities now have waiting lists of 6 months or more

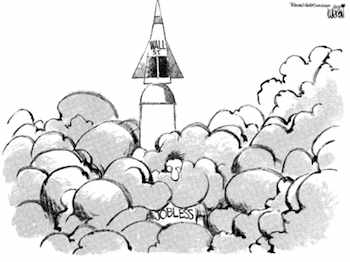

The crowds of unemployed people trying to get retraining have so swamped long-underfunded community colleges and other job skills programs that many communities now have waiting lists of six months or more.

The programs that are supposed to pay for retraining of unemployed workers are crowded even though the Obama administration has raised the annual federal training budget by $200 million to $3.8 billion in 2010 and added a $4.5 billion infusion in extra training funds in the 2009 stimulus bill. President Obama has said he wants "to fundamentally change our approach to unemployment in this country, so that it's no longer just a time to look for a new job, but is also a time to prepare yourself for a better job."

Unfortunately, those big dollar numbers have been no match for the dramatic increases in jobless who want retraining. The number of unemployed Americans has more than doubled in the past two years to 14.4 million. Under the normal budget, that leaves only about $250 per year in training funds per unemployed American. The one-time infusion of extra stimulus money added the equivalent of $312 or so per unemployed person, which is tiny when considering that one semester at a typical community college costs about $1,700 in tuition and books.

What's more, some of those who might be able to collect training funds are being turned away from overcrowded community colleges.

"Frankly, I am stunned," says Anthony Carnevale,

director of the

Any adult -- employed or not -- who wants help funding education can apply for regular financial aid. But aid pays only for courses that lead to a degree, and many short-term training programs don't qualify. Besides, education grants generally go just to low-income students who haven't yet earned a bachelor's. Other adults in school are usually offered only low-interest student loans.

Those who can't get financial aid, or whose aid is not enough, can apply for federal retraining funds through their local One-Stop Career Center. Those who can prove they lost their job due to foreign competition may receive training funding through the federal Trade Adjustment Act. But those who've lost their job for other reasons will likely have to spend week or months proving they can't find a job at a living wage in their field to qualify for training funding under the Workforce Investment Act. Normally, a majority of the jobless don't need full retraining to find another job. But so many people have lost their jobs, so many industries have been flattened, and rising tuition has raised the cost of retraining so high that many communities have run out of WIA training money.

By late 2009, the One-Stop Career Centers in southwest

Wisconsin, for example, had already spent almost

every penny of the $2.9 million training budget that was

supposed to last until June 30. Starting January

1, all new training applicants are being placed on waiting

lists, says Robert Borremans, executive director of the

Things are similarly dire in Kansas, where

"there is a system breakdown," worries Chris Cannon,

chair of the

There are also about 1,000 workers on waiting lists for retraining in

Flint, Mich., says Michael Kelly,

a spokesman for

Even those who manage to qualify for funding can have trouble getting into classes. Community colleges across the country are having to cut their budgets while working to accommodate thousands of laid-off adults trying to strengthen their résumés. The Miami-area community college system, for example, estimates that about 5,000 students couldn't enroll in any of the classes they wanted in the fall of 2009. About 30,000 were shut out of at least one of the classes they tried for, says Dulce Beltran, registrar. And in North Dakota, there are waiting lists for popular training programs such as welding.

Waiting lists aren't universal, however.

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMY | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Jobless Overwhelm Retraining Programs | Kim Clark