- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: World

The Global Militarisation Index

by Max M. Mutschler and Jan Grebe for Bonn International Center for Conversion (BICC)

How do you determine if a society is too militarized? What's driving high levels of militarization in different parts of the world? Finally, what's the relationship between militarization and human development? The answers to these question and others can be found in the latest edition of the Global Militarisation Index.

Compiled by BICC, the Global Militarisation Index (GMI) presents on an annual basis the relative weight and importance of a country’s military apparatus in relation to its society as a whole. The 2015 GMI covers 152 states and is based on the latest available figures (in most cases data for 2014). The index project is financially supported by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

There are numerous sources of conflict around the world that are driving militarisation in many regions and inducing states to modernise their armed forces or increase defense budgets. Among the ten countries with the highest level of militarisation — namely Israel, Singapore, Armenia, Jordan, South Korea, Russia, Cyprus, Azerbaijan, Kuwait and Greece — three are in the Middle East, two in Asia and five in Europe.

The United States and China are absent from the GMI Top 10, despite being global leaders in military spending. This is because when their military expenditures are measured as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP), and their military headcount and heavy weapon system numbers are measured per 1,000 inhabitants, the situation looks rather different. Nevertheless, they are following the trend towards restructuring and modernisation of the armed forces.

The region with the highest level of militarisation is again the Middle East. This upward trend must be seen in connection with the violent conflicts across the region — the Israel–Palestine conflict, the war in Yemen, the civil war in Syria and the regional threat posed by so-called Islamic State (IS).

In Europe, too, we find high levels of militarisation. Current crises, not least the war in eastern Ukraine, could become the factor that will push up defense budgets in the future. There is also a local arms race between Armenia and Azerbaijan triggered by the Nagorno–Karabakh conflict.

Included for the first time in the 2015 GMI report is an examination of the relationships between militarisation and human development by considering the Human Development Index (HDI). For stronger economies, we find that a high GMI ranking is often accompanied by a high HDI value (Israel, Singapore). The relationship between militarisation and human development may again differ in countries where a high GMI is combined with a low HDI, such as Chad, or Mauretania. Here, disproportionately high spending on the armed forces may be taking critical resources away from development.

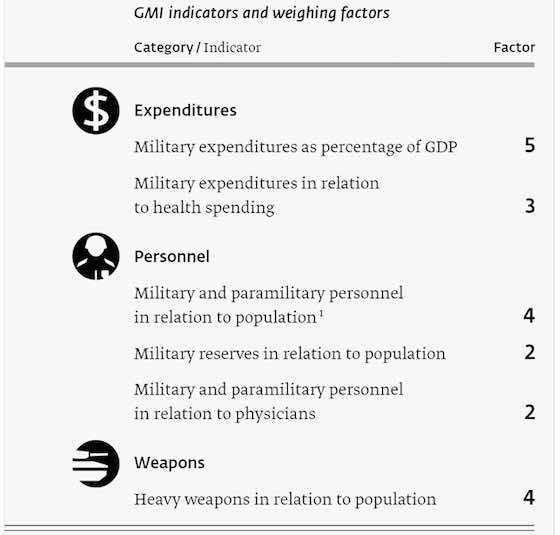

Methodology of the Global Militarisation Index (GMI)

The Global Militarisation Index (GMI) depicts the relative weight and importance of the military apparatus of one state in relation to its society as a whole. For this, the GMI records a number of indicators to represent the level of militarisation of a country:

- the comparison of military expenditures with its gross domestic product (GDP) and its health expenditure (as share of its GDP);

- the contrast between the total number of (para)military forces and the number of physicians and the overall population;

- the ratio of the number of heavy weapons systems available and the number of the overall population.

GMI Indicators & Weighing Factors

The GMI is based on data from the Stockholm Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Institute for Strategic studies (IISS) and BICC. It shows the levels of militarisation of 161 states since 1990. BICC provides yearly updates.

In order to increase the compatibility between different indicators and to prevent extreme values from creating distortions when normalising data, in a first step every indicator has been represented in a logarithm with the factor 10. Second, all data have been normalised using the formula x=(y-min)/(max-min), with min and max representing, respectively, the lowest and the highest value of the logarithm. In a third step, every indicator has been weighted in accordance to a subjective factor, reflecting the relative importance attributed to it by BICC researchers (see Graph below). In order to calculate the final score, the weighted indicators have been added up and then normalised one last time on a scale ranging from 0 to 1,000. For better comparison of individual years, all years have finally been normalised.

The GMI conducts a detailed analysis of specific regional or national developments. By doing so, BICC wants to contribute to the debate on militarisation and point to the often contradictory distribution of resources.

BICC GMI

Militarisation remains a controversial concept. The GMI is deliberately designed to avoid the normative assumption that militarisation always means an excessive emphasis on military power, or that very high resource allocations necessarily have negative consequences for security or for overall social development. Instead, the GMI approach does not only consider the scale of resources allocated to the military but relates them to the wider society. Among other criteria factored into the Index are the proportions of gross domestic product (GDP) spent on the military and spent on health.

Numerous sources of conflict across the world continue to fuel the arms dynamic in many regions and cause governments to modernise their armed forces or increase their defense budget. Apart from rivalries between states, such conflicts largely involve internal armed struggles, civil wars, uprisings, unresolved territorial disputes, military confrontations and anti-piracy operations, but also the desire to project military power in the service of one interest or another. Arms build-up is emerging as a trend in many parts of the world. Governments perceive the threats facing their country in different ways, and these are key in determining the way armed forces are set up and equipped. But the conditions and triggers for strengthening or modernising the military are often different, and the changes in level of militarisation on the GMI values vary from country to country and from continent to continent.

In this 2015 GMI we will seek to analyse some of the current militarisation trends more closely.

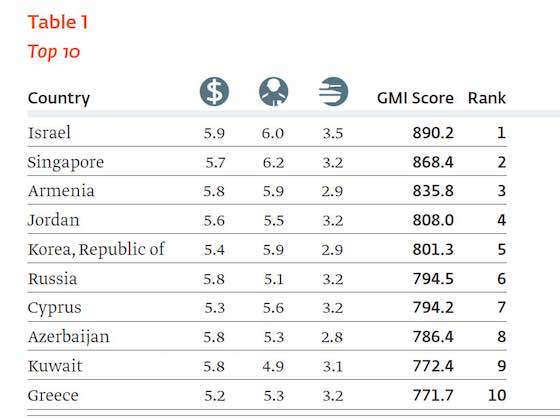

The Top 10

Among the ten countries with the highest levels of militarisation — Israel, Singapore, Armenia, Jordan, South Korea, Russia, Cyprus, Azerbaijan, Kuwait and Greece — three are in the Middle East, two in Asia and five in Europe.[2] In these countries, the armed forces are resourced particularly strongly compared to other sectors of society.

By contrast, a number of major states and emerging economies are not found among the GMI Top 10. The United States, for example, is only ranked 29.

Top 10 countries with the highest levels of militarisation

Although it clearly has the world’s biggest defense budget and a very large army, the resources allocated to the military are relatively moderate in relation to overall public expenditure, health spending and population size. Be that as it may, the United States accounted for 34 per cent of worldwide military expenditure in 2014, having spent US $610 billion.[3] On the one hand, this share has been falling over recent years and may shrink further in the course of the US administration’s austerity measures, so we could see successive changes in the level of militarisation for the United States. Moreover, the army will probably be numerically downsized with the end of US engagement in Afghanistan and Iraq. On the other, none of this will alter the country’s overall global military supremacy. Indeed, much of the attempted consolidation, especially in the army, is part of restructuring and modernisation to improve capability in future missions.

Regional armament in focus

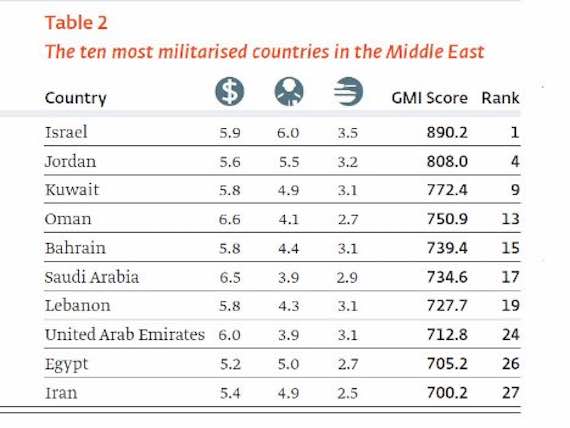

Middle East

The Middle East remains a region in which most countries are highly militarised. Israel is again ranked above all other countries (position 1), a level of militarisation that is partly explained by its decades-long conflict with the Palestinians and the efforts by a number of Arab countries to build up their military capability that are regarded by the Israeli government as a serious threat. The resources available to the military are disproportionately high by international comparison. Israel’s military expenditure last year amounted to 5.2 per cent of GDP, a considerable economic burden on the country. And, against the background of the country’s security environment, Israel has a system of compulsory military service in which most Israelis are required to serve for three years. This enables the government to draw on a very large military reserve, now numbering 465,000 soldiers, in the event of war. For every 1,000 inhabitants in Israel there are 22.9 soldiers and paramilitaries, which is a very high ratio (for comparison, Germany: 2.3), and only 3.1 physicians (2012 data).

The 2015 GMI lists Jordan in fourth place. In terms of numbers, Jordan has 17.9 soldiers and paramilitaries, but only 2.5 physicians for every 1,000 inhabitants (2010 data). The country’s high level of militarisation is partly explained by the Israel–Palestine conflict. Jordan’s security environment has become increasingly precarious in recent years, not least due to the upheavals in North Africa, the impact of the Syrian civil war and the regional threat posed by the socalled Islamic State. These developments may drive further militarisation. Similar factors apply to Kuwait (position 9) where there are 6.7 soldiers and paramilitaries per 1,000 inhabitants but only 1.5 physicians.

The multiple and complex conflicts occurring across the region are a key factor behind the build-up and modernisation of armed forces in which a number of states are investing their considerable oil wealth. Financial reserves accumulated in the years of high oil prices are being used to equip armies with the latest warplanes and weapon systems, not least missile defense systems. Even though the currently low price of oil has significantly reduced the revenue flows to many governments in the region, it is having little impact on military expenditure. defense budgets remain high, for the time being, as financial reserves are used to make up the loss in revenues. If, and this is seen as likely, defense spending continues to rise over the next few years there will probably be cuts in the financial resources available to other sectors of society.

Saudi Arabia (position 17) is a case in point. The level of militarisation by the Gulf monarchy is probably connected with its enhanced engagement in the region, as seen most notably in the recent military intervention in Yemen and operations against socalled Islamic State (IS). Saudi military expenditures are rising, standing at 10.4 per cent of GDP in 2014. Even though the government’s revenues are waning, procurement of modern weapon systems remains at a high level, whereas the share of GDP spent on health has been shrinking in recent years (2013: 2 per cent). A strong focus of arms spending is air force modernisation, with combat and tanker aircraft being purchased to improve the Kingdom’s operational radius.

A similar case is Qatar (2013: position 57). Although there are no figures available for 2014, the emirate is likely to show rising levels of militarisation in future after its announcement in 2014 of a US $24 billion investment in modern weapon systems. This pushes up military spending sharply, taking a larger proportion of GDP than ever before and a shifting the ratio between heavy weapon systems and population size.

Bahrain (position 15), Kuwait (9) and Oman (13) — countries with a relatively high level of militarisation — are also having to contend with a low oil price. In Kuwait, around 91 per cent of government revenues are generated from oil sales. Although firm evidence of rising military spending in the form of specific arms procurements is not yet available, the conflict in Yemen may be driving militarisation, especially in Oman.

Top 10 countries in the Middle East

Sub-Saharan Africa

The Index records militarisation in most of Sub-Saharan Africa at quite a low level. Apart from Angola, the region’s highest ranking country (position 31), the exceptions include Mauretania (position 41), Chad (position 42) and Namibia (position 44).

Angola has traditionally maintained a large army. Having gone through a long civil war, its armed forces occupy a strong position within state and society and exercise a great deal of influence. The government, which has enjoyed high revenues from oil sales over the years, is making large investments in modernising the armed forces, which explains the high level of militarisation. In particular, Angola has procured new aircraft and helicopters from Russia as well as from Brazil, the Czech Republic and the United States. Additional air power is intended to secure the borders and control coastal waters. Military expenditures as a proportion of gross domestic product now comes to 5.2 per cent, a rise of 1.7 per cent since 2011, while health spending amounts to just 2.5 per cent of GDP, a rise of only 0.3 per cent. (As for personnel numbers, the latest available figures are from in 2009 and show just 0.1 physicians but 5.5 soldiers and paramilitaries for every 1,000 inhabitants.) Not only procurement of weapon systems but also their maintenance and operation is expensive, binding additional resources over long periods — resources badly needed in other fields in a country of widespread poverty. Over 50 per cent of Angolans still live on less than two US dollars a day.

Nigeria, militarily the strongest country in West Africa, has, by contrast, a low GMI ranking (position 138). This is because Nigeria spends just 0.4 per cent of GDP on the military; and for every 1,000 inhabitants there are 0.9 soldiers and 0.3 physicians. In view of the country’s numerous internal conflicts, such a low level of militarisation appears surprising. After all, a violent conflict has plagued the Niger Delta for many years, growing piracy in the Gulf of Guinea threatens the whole region, and the Boko Haram terrorist group is creating mayhem in the north of the country. Yet Nigeria invests relatively little in its armed forces. The country is however engaged in large-scale naval procurements as a response to the threats in the south and is equipping the army with new armoured vehicles for the fight against Boko Haram. This may be reflected in a higher GMI level in future years.

Militarisation in Europe

A large number of countries in Europe show an average level of militarisation, although their GMI rating could change in the future.

Europe’s most militarised countries

Two European counties have strikingly high levels of militarisation: Armenia (position 3) and Azerbaijan (position 8). Against the background of the ongoing Nagorno–Karabakh conflict, both countries are still investing their resources to an inordinate degree in expanding and modernising their armed forces. The same can be said of Greece and Cyprus, still ranking high in the GMI. A key factor here is probably the enduring perceptions of a threat posed by Turkey. Even the leftist Syriza government has apparently not fundamentally called this view into question. Although Greece has been forced to make major cuts in its defense budget over the last few years, the numbers show that there are still 13.5 soldiers and paramilitaries per 1,000 inhabitants. In contrast, the figure for physicians came to just 4.3. Moreover, Greece has around 1,350 heavy battle tanks, constituting by far the biggest fleet of tanks in Europe.[4]

Western Europe

Whereas in the past few years military spending was cut back in western Europe, in particular, in the course of austerity measures to shore up hard-hit public finances, new tensions, especially the war in Ukraine, have become a driver for a future upturn in defense spending. Thus, spending on military procurements and equipment by European NATO states fell between 2010 and 2014 by around US $14 billion, but NATO estimates suggest there will be a significant rise in 2015.[5] The organisation aims at an increase of military budgets to two per cent of the GDP. This change of direction will impact over the medium and long-term on militarisation levels if bigger procurements really are made and heavy weapon arsenals are restocked. In western Europe, France (position 59), the Netherlands (position 101), Norway (position 38), Sweden (position 100) and Germany (position 97), for example, have pledged to raise defense expenditures year by year in the future.

In the case of Germany, a strong economy means that increases in defense spending are likely to be accompanied only by a very slight change in the military share of GDP, which currently stands at about 1.2 per cent. The military expenditures of most western European states, with the exception of France (2.2 per cent) and Greece (2.2 per cent), account for less than two per cent of their respective GDP.

Top 10 countries in Europe

Eastern Europe

A number of eastern European states have also announced plans to boost military spending. After years of cut-backs, the Czech Republic (position 111) wants to increase military expenditures from the current 1 per cent share of GDP to 1.4 per cent by 2020. Lithuania (position 63) is committed to reaching the target of 2 per cent called for by NATO within the same timeframe. Romania (position 34) and Bulgaria (position 28) are planning similar increases in the years to come. The question of what financial scope exists for actually putting desired increases into practice remains open. It is not yet clear whether and how far the level of militarisation of European states will change. For one thing, the process of downsizing armies means fewer soldiers in service. Moves to abolish or suspend conscription, as occurred in Germany and Sweden, mean fewer reservists will be available in the medium to long-term. By contrast, Lithuania announced in February 2015 that compulsory military service, revoked back in 2008, will be reintroduced, initially for the next five years. This will alter the GMI parameters.

Russia has moved down one position on the previous year and is now ranked 6th. Russian military expenditures for 2014 totalled US $84.46 billion, which constitutes a 4.5 per cent share of gross domestic product. The number of military personnel in service, including those in paramilitary formations, amounted to 1,260,000, and Russia also has two million reservists. It is the numerically large forces, combined with large numbers of heavy weapon systems that explain Russia’s high ranking in the GMI, well ahead of, say, the United States or China.

In the wake of the 2008 war in Georgia, which exposed the shortcomings of the Russian Army, Russia launched a reform process in the armed forces with a strong focus on modernisation. Smaller, more professional and more mobile units are to increasingly replace the massed ranks of conscripts. Further steps are to be taken to strengthen special operations capabilities. Russian weapon systems are also being upgraded. Key elements in this modernisation are likely to be air force improvements, new precision weapons and automatic command systems as Russia seeks to at least narrow the gap with the military development in the United States. Looking to the future, we will probably see Russia following a similar pattern as that of the United States and China, of reducing troop numbers. It does not signal a reduced role for the military but, rather, a modernised army.

Just how far the conflict with Ukraine and the resulting deterioration of relations with NATO will affect the level of militarisation in Russia can for the time being only be a matter of speculation. We may, however, assume that Russia will at least continue, if not strengthen, its efforts to modernise the armed forces.

The ranking of Ukraine in the GMI has shifted only a little, from 24 in 2013 to 22 in 2014. But it is too soon to tell how far the present conflict will have an impact on the country’s level of militarisation over the longer term.

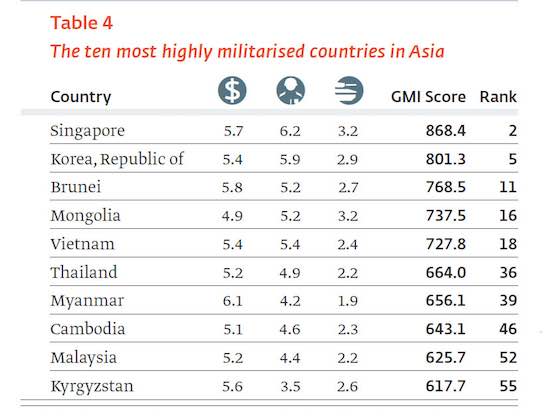

Militarisation in Asia

China, the leading military power in Asia, is ranked 87th in the 2015 GMI. China’s considerable growth in military spending (US $216 billion, according to SIPRI, second only to the United States) has gone hand in hand with the country’s continuous economic growth. Economic expansion explains why military expenditure as a proportion of gross domestic product comes to only around 2 per cent despite growing in absolute terms over many years. As for spending on health, this stood at 3.1 per cent of GDP in 2013, an increase of around 0.2 per cent since 2010.

The Chinese leadership has recently announced plans to downsize the armed forces by 300,000 by the end of 2017, which will leave around 1.9 million soldiers in service. This will affect the level of militarisation and free up resources over the medium to longterm. However, it is also likely savings will then be invested in developing and procuring modern weapon systems for the Chinese Air Force and Navy as part of the ongoing modernisation. Modernisation costs together with investment in military research and development will probably entail a further expansion of China’s defense budget.

Singapore, a country that ranks in second place in the GMI list, has one of the most powerful armed forces in the region. Despite its small size, Singapore maintains state-of-the-art weapon systems in large numbers and a large army. Most neighbouring countries, with the exception of China and India, have come to regard Singapore’s military as qualitatively and quantitatively superior. Military expenditures are 3.3 per cent of GDP, representing a very high share in regional comparison. In view of Singapore’s relatively small population, its armed forces could be regarded as numerically oversized, since there are as many as 27.3 soldiers, but only 1.6 physicians, for every 1,000 inhabitants. The magnitude of the country’s forces and their equipment must be understood in connection with the strategy of total defense pursued by the political and military leadership since the 1980s.

Top 10 countries in Asia

In South Korea, which ranks 5th in the GMI, the conflict with North Korea[6] is the critical factor behind its military doctrine and the alignment of its armed forces. Despite the recent diplomatic overtures, the two countries are still officially at war. South Korea has a comparatively large army, with 659,500 soldiers and paramilitaries. This breaks down to 13.1 for every 1,000 inhabitants, compared to only 2 physicians. defense expenditures amount to US $36.7 billion, which is a 2.6 per cent share of GDP. The border between North and South Korea is one of the most highly militarised zones in the world. Interestingly, the South Korean defense doctrine also assumes a tous azumuts threat scenario, envisaging potential attacks from Japan or China in the event of Korean reunification.

Militarisation and human development

The GMI tells us about the resources devoted to a state’s armed forces, showing which countries have particularly high or low levels of militarisation. The use of major resources for military purposes does not automatically mean a loss of economic potential. It is also possible for public expenditures on the military or the mobilisation of previously unused labour to act as an economic stimulus. Providing soldiers with a regular income generates purchasing power, while infrastructure investments for military purposes may also benefit the wider population. Yet, funding for the armed forces ties down resources that could be invested in more productive sectors of society and the economy, such as education, health and sustainable electricity supplies.

To explore this relationship we have correlated the GMI with the Human Development Index (HDI). The latter distinguishes between very high, high, medium and low human development in each country. The following section considers the possible connections between social and economic development, measured by the HDI[7], on the one hand, and a country’s level of militarisation, measured by the GMI, on the other. The correlations presented here do not, however, automatically suggest causalities.

A. High militarisation and high human development

The figures show that highly militarised countries tend to have a high level of human development. An obvious reason for this would be that many of these countries have sufficient resources to invest in the military without significantly hampering economic development. A clear case in point is Israel, Singapore or the Republic of Korea. These states stand at the top of the GMI but also belong to the group of countries with a very high HDI.

GMI in relation to HDI

B. Low militarisation and low human development

At the other end of the spectrum we find states such as Liberia, Gambia or Sierra Leone, which display both a low level of militarisation and a low level of human development. Take the case of Liberia and Sierra Leone, which have both emerged from civil wars and rank in positions 149 and 146 respectively. Both countries have significantly cut back on their armed forces as a post-conflict environment and are to some extent still involved in a restructuring process. They have hardly any heavy weapon systems and spend only 0.8 and 0.6 per cent respectively of gross domestic product on the military. By comparison, health spending in Liberia amounted to 3.6 per cent of GDP in 2013, and in Sierra Leone even as much as 1.7 per cent.

So this poses the question of how low levels of militarisation might affect society in terms of human development. A very low level of militarisation can be an indication of fundamental shortcomings in the security apparatus that prevent the emergence of a secure and stable environment needed for economic development. While there can hardly be a purely military solution to the multiple and complex conflicts across West Africa, it is also true that conflicts cannot be effectively contained by weak or even dysfunctional armed forces. In this situation, a low level of militarisation has negative consequences for human development.

Conversely, however, the low level of human development may indicate that a country has very meagre resources overall and therefore has very little to invest in its armed forces. But, again, this is not necessarily the case.

C. High militarisation and low human development

In some countries, such as Angola, Chad and Mauritania, we can observe a relatively high level of militarisation (position 31, 42 and 41 respectively in the GMI) accompanied by low human development. Here, the relationship between militarisation and human development may entail disproportionally high spending on the armed forces draining resources that are vital for development.

D. Low militarisation and high human development

There are some interesting examples that show it is possible to keep militarisation at a low level while achieving a comparatively high level of human development. Iceland, Malta and to a lesser extent Albania are such cases. In the GMI they are ranked in positions 143 (Malta), 144 (Albania) and 151 (Iceland), placing them among the world’s least militarised countries. Yet at the same time they enjoy high or even very high human development.

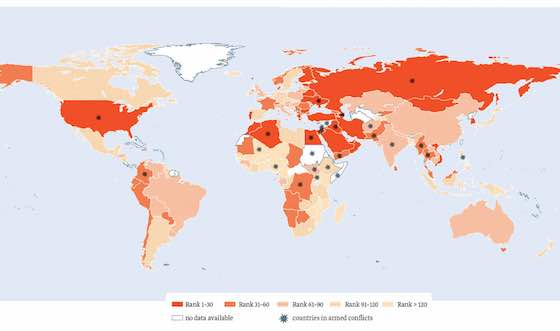

Map: Overview GMI-Ranking worldwide (Source conflict data: UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset ; sources of administrative boundaries: Natural Earth Dataset).

The depiction and use of boundaries or frontiers and geographic names on this map do not necessarily imply official endorsement or acceptance by BICC.

MILITARISATION INDEX RANKING

Rank Country

1 Israel

2 Singapore

3 Armenia

4 Jordan

5 Korea, Republic of

6 Russia

7 Cyprus

8 Azerbaijan

9 Kuwait

10 Greece

11 Brunei

12 Belarus

13 Oman

14 Algeria

15 Bahrain

16 Mongolia

17 Saudi Arabia

18 Vietnam

19 Lebanon

20 Morocco

21 Finland

22 Ukraine

23 Turkey

24 United Arab Emirates

25 Estonia

26 Egypt

27 Iran

28 Bulgaria

29 United States of America

30 Portugal

31 Angola

32 Serbia

33 Yemen

34 Romania

35 Chile

36 Thailand

37 Iraq

38 Norway

39 Myanmar

40 Peru

41 Mauritania

42 Chad

43 Congo, Republic of

44 Namibia

45 Sri Lanka

46 Cambodia

47 Denmark

48 Macedonia

49 Botswana

50 Ecuador

51 Montenegro

52 Malaysia

53 Switzerland

54 Pakistan

55 Kyrgyzstan

56 Guinea-Bissau

57 Georgia

58 Colombia

59 France

60 Paraguay

61 Slovenia

62 Uruguay

63 Lithuania

64 United Kingdom

65 Hungary

66 Afghanistan

67 Australia

68 Poland

69 Gabon

70 Burundi

71 Bolivia

72 Austria

73 South Sudan

74 Croatia

75 Brazil

76 Fiji

77 Tunisia

78 El Salvador

79 Kazakhstan

80 Italy

81 Honduras

82 Latvia

83 India

84 Venezuela

85 Moldova

86 Laos

87 China

88 Nepal

89 Equatorial Guinea

90 Guinea

91 Indonesia

92 Spain

93 Belgium

94 Canada

95 Congo, DR

96 Slovakia

97 Germany

98 Rwanda

99 Zambia

100 Sweden

101 Netherlands

102 Bosnia and Herzegovina

103 New Zealand

104 Guyana

105 Togo

106 Tanzania

107 Nicaragua

108 Philippines

109 Guatemala

110 South Africa

111 Czech Republic

112 Senegal

113 Japan

114 Ethiopia

115 Argentina

116 Luxembourg

117 Ireland

118 Libya

119 Cote D‘Ivoire

120 Mexico

121 Cameroon

122 Bangladesh

123 Mozambique

124 Tajikistan

125 Kenya

126 Dominican Republic

127 Benin

128 Zimbabwe

129 Lesotho

130 Mali

131 Burkina Faso

132 Belize

133 Mauritius

134 Jamaica

135 Niger

136 Ghana

137 Madagascar

138 Nigeria

139 Seychelles

140 Uganda

141 Malawi

142 Timor-Leste

143 Malta

144 Albania

145 Trinidad / Tobago

146 Sierra Leone

147 Cape Verde

148 Gambia

149 Liberia

150 Papua New Guinea

151 Iceland

152 Swaziland

Notes

[1] The main criterion for coding an organisational entity as either military or paramilitary is that the forces in question are under the direct control of the government in addition to being armed, uniformed and garrisoned.

[2] Syria was also ranked among this group of countries in recent years, but the civil war has made it impossible to draw on reliable data about resources going to government forces. We may, however, assume that, with the Syrian regime mobilising extensive resources, the level of militarisation in Syria is very high and will have again risen as the war unfolds. In the case of North Korea and Eritrea, very high levels of militarisation can also be assumed. No valid data is available for either country.

[3] Figures on military expenditure by individual countries are based on data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

[4] Germany has reduced its stocks of heavy battle tanks over the last 25 years by around 2,000 units. At present some 225 heavy battle tanks are in active service, although the Bundeswehr plans to increase this number slightly in view of the latest developments in Europe.

[5] http://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2015_06/20150622_PR_CP_2015_093-v2.pdf

[6] Although North Korea is likely to have a very high level of militarisation, no valid data is available.

[7] The HDI values refer to 2013 data (i.e. the latest figures available).

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Article: Courtesy The International Relations & Security Network.

World News: "The Global Militarisation Index"