- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

By Paul Kennedy

Over the past year, a group of disaster-relief and development-aid workers began the construction of some schools in the war-torn eastern Congo. As it happens, one of the administrators of this project is my eldest son, Jim Kennedy, so the family has received a stream of digital photos of schools halfway through construction, of groups of young boys delightedly learning the art of finger puppetry, and of other signs that things are improving.

I frequently shake my head at what this says, in an encouraging way, about our global interconnectedness: Here is a project funded by the

Then there is the bad news. A few months ago, it became somewhat more difficult to maintain the school-building program, when close to 100,000 Rwandan refugees swarmed across the border, out of fear of the advancing

These international relief workers were lucky. At about the same time, the Taliban deliberately attacked and killed five U.N. election monitors in Kabul, to disrupt the chances of any free and fair elections. A few weeks earlier, at the beginning of October, five members of the World Food Programme were killed by a suicide bomber in Islamabad. The heroic frontline staffs of international civil society are being intentionally assaulted by the forces of chaos and hatred. One is reminded of John Buchan's sobering comment: "Under the thin crust of civilization, the primal voices murmur." And lash out.

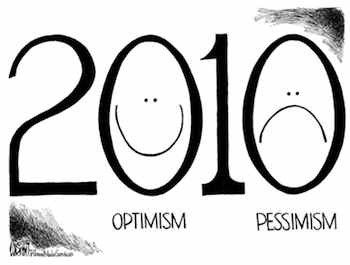

Things are happening across our planet that should cause all sensible observers to be troubled. On the one hand, there are signs of progress and growing prosperity in countries ranging from Canada to China, from Australia to Brazil: the impressive new technologies; the enhanced flow of international exchanges, in the form of capital, visible goods, invisible service, tourists, students and knowledge exchanges. On the other hand, there are the many indicators of disruptive tendencies, of environmental catastrophes, financial instabilities, currency turbulences, civil wars and the trade in small arms that fuels them, failed states, quarrels over contested historic lands and borders, human-rights abuses, and displays of angry, egoistic nationalism. It is not a pretty sight.

How to explain this baffling phenomenon of simultaneous global integration and tribal disintegration? It is not the first time this paradox has displayed itself. Back in October 1930, thus after the Wall Street crash but before the fascist aggressions, the London-based Economist expressed its deep anxiety at the way global economics and national politics were falling out with each other:

"On the economic plane, the world has been organized into a single, all-embracing unit of activity. On the political plane, it has not only remained partitioned into 60 or 70 sovereign national states, but the national units have been growing smaller and more numerous and the national consciousnesses more acute. The tension between these two antithetical tendencies has been producing a series of jolts and jars and smashes in the social life of humanity."

The Economist's description was not entirely accurate (the USSR could hardly be seen as a part of a single all-embracing world economy, for example), but in its general drift the writer was onto something. Bankers, investors, exporters, shipping lines, new air routes and cable communications seemed to be bringing societies closer together into what Wendell Wilkie would later (in the title of his 1943 bestseller) call "One World."

But the political world was much more fractured, by border rivalries, ethnic and religious antagonisms, Great-Power maneuverings, breakaway movements, anti-Western agitations and then colonial crackdowns. With the Smoot-Hawley tariff, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the failure of the

And what of today? Were one called upon to explain to a fact-finding mission from Mars what the economic and political state of our globe is as we enter 2010, we would have to report on a whole slew of contemporary paradoxes and explain to the bewildered Martians that the signs for the Earth's future point in many different directions.

At the technological level, for example, the caravan of progress continues to move ahead and, indeed, at the speed of a Maglev train rather than a traditional camel train or even an automobile. Not a day goes by without the announcement of some newer forms of mobile phones, enhanced speed of message transmissions, breakthroughs in medical techniques, and amazing advances in imaging, extraction technologies, oceanography, environmental sciences and the like. Even the average layperson, content with reading the Science page of The

Yet if one looks to the harder-nosed, accounts-driven worlds of finance and trade, taxes and spending, the scene is a lot more confused: There are indeed many "jolts and jars," which the subprime market/banking/company collapses of the past 18 months confirmed, which is not to say that they were the sole cause of our present economic disarray. It is as if that noble galleon, the S.S. Global Economy, had ridden into a hefty storm, been severely battered by waves and winds coming from various directions, but is still afloat albeit with a lot of top-hamper (Lehman,

Just to begin with one turbulent current, the trade imbalances seem dangerously tilted.

And, while China will surely be pouring a lot more money into critical domestic items such as housing, power plants, harbors and railways, not to mention its burgeoning armed forces, the consequence will be that it will shift hundreds of billions of its export-surplus-earned dollar reserves back to the yuan, sending the U.S. currency even lower. Right now, we may not be far from a global currency crisis, with Asian governments and sovereign wealth funds -- not to mention speculators -- wavering on the brink of a decision to buy gold and sell dollars, as India recently did. With learned op-eds and editorials in virtually every newspaper across the globe talking about this, the chances of volatility increase. Buchan's phrase might suitably be modified: "Above the thin crust of a self-balancing free-market system, the kites and vultures shriek."

As to our world of politics, well, we would have the greatest difficulty in explaining to the Martian visitors why we are the way we are -- 192 separate states, some disintegrating -- and how that came to be. For odd historical reasons, the 6.5 billion humans on our planet have divided themselves into a ridiculously large number of separate nations, large and small, rich and poor, peaceful and war-torn, each touting their national flags, insignia, anthems, armed forces, customs and immigration offices, and the rest. Perhaps this would be tolerable if all nations lived in harmony with nature, like the birds of the air or the grazing animals. But we do not. Right now, that unfolding war in the eastern Congo/Rwanda is one of 20 or so that U.N. peacekeepers are trying to deal with -- and that does not include the spreading fires of the quintuple Iraq/Iran/Afghanistan/Pakistan/Kashmir tangle.

Moreover, we still experience the age-old challenge of "the rise and fall of nations": Only rarely does a Great Power descend into the second division without a fight; and only rarely does a rising power get through to the top without violence. Many an American naval and air-force planner nowadays is actually not paying much attention to Afghanistan, for they have China on the brain. And many a Chinese naval planner is figuring out a "sea-denial" strategy, to keep America out of East Asia.

At this stage, the Martians will surely have decided to go home. The Earth is not a sensible place for intelligent life to occupy -- good for ever-smarter BlackBerrys no doubt, less friendly to the real blackberries along the wayland tracks, and a rather unhappy place economically for most members of that dominant species, homo sapiens. And it is not good to be in the many Gomas of the world.

But, unlike the Martians, we have to stay here, in our confused and spatchcocked political, economic and technological circumstance, with the more dedicated of our political leaders, international civil servants, banks, and opinion makers seeking to make things better, or at least ensuring that things don't go from bad to worse.

There has been a lot of progress on the planet over the previous decades, and there beckons to be more in the future. But there are also many storms, tides and rocks ahead, which is why, again and again, we will turn to our national governments and international organizations, however flawed, however human, to keep the global ship of state afloat -- and capable of sailing onwards. Still, no one should assume that it will be an easy voyage.

© Paul Kennedy

WORLD |

AFRICA |

ASIA |

EUROPE |

LATIN AMERICA |

MIDDLE EAST |

UNITED STATES |

ECONOMICS |

EDUCATION |

ENVIRONMENT |

FOREIGN POLICY |

POLITICS

World - Integration and Disintegration: The Future of Our Puzzling World | Paul Kennedy