- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Video Games

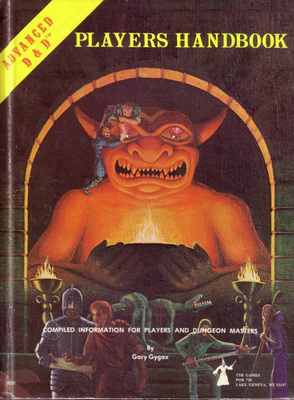

Looking back on "Dungeons & Dragons": Did videogames actually start with pen, paper and 20-sided dice?

In my local game store, they have a bumper sticker that reads:

I PLAYED D&D BEFORE IT WAS COOL

The slogan was well aimed, and I felt myself standing up a little straighter and boasting to myself: Why, yes, I DID play D&D before it was. . .¦

Cool?

Popular culture has a funny way of turning around and talking you into things that are just not true -- that "Lost" really is a metaphor for postmodern life; that clip-on ties are so coming back with the hip kids in Brooklyn; that Lady Gaga didn't steal every good idea she had from Mathew Barney and Bjork; and that "Dungeons & Dragons" has been, or ever will be, cool. Then again, there's something to be said for a mainstay of geek culture that has survived for 35 years as a paragon of something to do in the basement that you can talk about the next day at school without shame. And looking back, it's clear that culture owes something to the old Dungeon Master, too. "D&D" isn't just the punch line for a "Jeopardy" question. The nerd DNA of "D&D" has woven itself virally into our everyday life.

"We think of fantasy differently than we did in the '70s," says Andy Collins, a guy who makes his living developing and editing "D&D" books for game publisher

"The idea of being someone else for a few hours has a pretty broad appeal, and when you combine that with the timeless tropes of fantasy -- that appeals to people on a fundamental level."

When Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson cooked up a little booklet of rules in 1974 for simulating knights battling goblins, they probably didn't realize that they were forging a cultural icon. This was before these boys up north from the frozen lands of Wisconsin and Minnesota decided to sue each other, before they almost went bankrupt, before

What they were really doing was assembling the raw material of nerd culture into something that could be carried into the mainstream.

"When we look at our player base and beyond into our fan base, we see 24 million people in the U.S. 13 to 45 (years old) who played 'D&D' at one point," says "D&D" brand director Liz Schuh. "They might not play any longer, but think fondly of the franchise."

That's how "D&D" went from being something that kids in black trench coats played at school to being something that manly men like Hollywood hunk Vin Diesel and baseball superstar Kurt Schilling happily admit to enjoying. At a critical point in history, geek culture fused with pop culture to create a modern world that seems oddly like the fantasy-reality fusion of a William Gibson novel.

Maybe there was something in the air during the early '70s. Maybe it was historically inevitable. But it seems way more than convenient coincidence that Gygax and Arneson got their first packet of rules for "D&D" out the door in 1974, the same year Nolan Bushnell managed to cobble together a little arcade machine called "Pong."

We've never had fun quite the same way since.

Looking back, these two events set the today's world of gaming into motion -- the Romulus and Remus of modern game civilization. For the rest of forever, we would sit around and argue whether games should let us do more or tell us better stories. "Pong" never tried to put you in the role of an international athlete competing for cultural pride and a chance at that hot Swedish tennis player in the Olympic dorm next door. The story behind "Pong" didn't matter. And "D&D" players never quibbled about the game rules, because everyone knew the Dungeon Master would just summon some super kobold with a halberd and put everyone, and the story, back in their place.

Rules and stories would struggle for the soul of games ever after.

The funny thing is, we keep talking about games as systems of rules as if "Pong" were the rib of Adam from which all gaming life sprung. And in the process we sort of forgot about D&D.

But D&D never forgot about us.

If you were to randomly pick two influential titles out of the history of videogames and you ended up with "Akalabeth: World of Doom" and "Quake," you'd be very lucky -- since you'd have plucked two games that have their roots in "D&D." Richard Garriott's prototypical dungeon-crawler "Akalabeth" was his effort to hybridize his fascination with "D&D" and computers into an alchemical combination that would birth the computer role-playing game as we know it today. And "Quake" turns out to be the name of John Romero's "D&D" character, and the cult of multiplayer action that it spawned was a short 20-sided die roll away from the group fun of every dungeon party to venture into the mists of a "D&D" adventure.

"We saw a resurgence of interest in the game when the 'Lord of the Rings' movies came out," points out Schuh. "We also see people come in that have been reading fantasy novels, and some come in from digital gaming. We see people that play 'World of Warcraft' and say, 'Wow, this is really fun!' And then they come to the role-playing game, because it provides them even more choices as a player."

Game developers today can talk about user-generated content like they have discovered cold fusion and the perfect Margarita recipe. But "D&D" players have been merrily creating their own content since day one, keeping their adventures rolling along for years. "D&D" taught a generation of kids that they could make the games they play, and that nothing was more fun than getting together with friends for an evening of games. The videogame business has been trying to catch up ever since.

Brad King and John Borland in their book "Dungeons and Dreamers: The Rise of Computer Game Culture From Geek to Chic" trace the evolution of gamer culture out of "D&D," and find the old role-playing game as a sort of primordial soup of videogame life.

"It's almost impossible to overstate the role of 'Dungeons & Dragons' in the rise of computer gaming," they write in the introduction. "Scratch almost any game developer who worked from the late 1970s until today and you're likely to find a vein of role-playing experience."

Before "D&D," the idea that games could or should tell stories was a bit of an odd concept. Wrapped around hit points, armor classes, damage modifiers and character classes was the idea that fantasy literature was a good source of interactive fun, and a roll of the dice was a legitimate way to tell tall tales. These were not just innovative ideas; these thoughts were simply far out.

Now they are so much a part of our conception of games, we forget what a radical notion it was that stories and games could work together.

What is "BioShock" or "Fallout 3" other than a contemporary form of "D&D" with a robot Dungeon Master attempting to keep the story interesting? Or where would Harry Potter be if college kids hadn't made walking around in cloaks and carrying plus-3 Staffs of Smiting somehow seem like something that might be fun?

Mass culture finally digested what "D&D" was selling. Along the way it pooped out some ridiculous things, like "D&D" cartoons and movies. It also produced some a few half-decent videogames and inspired some of the best games of all time ("Planescape: Tormen"t? Yes, please). "D&D" also kept itself viable to a standing wave of nerds, each generation taking in its own edition of the game.

So today we have "Dungeons and Dragons 4th Edition." Filled with rogues and tieflings and wardens, the game is pretty much unrecognizable to the old timers that relied on graph paper and a lot of improvisation to patch over the gaping holes in the game system. But even after you shell out the bucks for the new "Player's Handbook," volumes one and two; the new "Dungeon Master's Guide," volumes one and two; and the new "Monster Manual," volumes one and two, you find that the game pretty much remains the same -- even if it has gotten a tad more expensive. And more fun to look at.

"Because of videogames, we are more visual gamers," says Collins. "We are a more visual culture in general. So having those visual elements -- dungeon tiles and plastic miniatures -- helps make it feel a little more like a game people are used to seeing."

Through all the changes, though, "D&D" remains "D&D."

You're still in a dark, dank, musty tunnel. The sounds of water trickling though the cracks echo like the cackle of some unseen beast. There's a smell in the air. Orcs. You grip your sword tightly as a chill runs down your spine. They are coming. What do you do?

"There's a whole new generation that sees this as a normal thing to do in life -- not a weird thing," Collins enthuses.

OK. Maybe not weird. Maybe even awesome. But still not cool.

Available at Amazon.com:

Article: Copyright © iHaveNet

Video Games: Dungeons & Dragons - Get Your Geek On

Article: Copyright © Tribune Media Services