- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

Troy S. Goodfellow, Crispy Gamer Videogame Reviews

It all began the moment I joined

For a few years now, the social gaming sphere has been drawing talent from the "traditional" videogame industry. Last June, EA's former Chief Operating Officer John Pleasants became CEO of Playdom, a social/casual gaming studio that had already claimed gaming legend Steve Meretzky. Similarly, EA's founder Bing Gordon is a board member for industry leader Zynga, the company that recently opened an East Coast office headed by strategy-game guru Brian Reynolds. So what does the future hold for a game space dominated by clones, micropayment-dominated progress-bar games, and shallow game design?

Brian Reynolds, the designer of deep strategy classics like "Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri" and "Rise of Nations," may seem an odd fit with the much lighter fare on

"It's the current entertainment I am addicted to. They are games I enjoy playing, though I wasn't sure why at first. There was no real deep design here. Part of it was instant gratification, but also the voodoo of social networking."

A simple game of "Scrabble," for example, may start as a way to interact with an old friend you have not spoken to in years. That interaction may become a deeper social engagement -- you exchange news, rediscover old similarities or rivalries, and are soon regularly competing for high scores or a won/lost record.

But if invitations don't follow, the game may be a failure. And, given the Internet's viral nature, something new will always come along.

"We have to keeping making games (at Zynga)," says Reynolds, "Because they rise and fall. We continue to build a game even after it goes live. You have to keep adding to them. You cannot slow down game development."

It's this constant pace of developing, upgrading, and launching that separates social gaming from the traditional game industry. Where EA or Blizzard can spend millions of dollars on a team of hundreds, more than two years before a game hits shelves, social gaming companies can spend only weeks on a game, launch multiple betas to test new features, and adapt the game on the fly. The immense player base of these games keeps the pace viable, because there are so many avenues for monetization.

Brandon Barber, Zynga's vice president of marketing and another refugee from EA, explains that the size of the audience -- often in the millions -- means that traditional "eyeball" metrics and Internet advertising can be as important to the bottom line as the in-game sale of items. The business model has been so successful that he expects the big interactive media players to soon break into the social gaming market.

"EA,

PopCap, America's most famous casual-game developer, is one of the big players trying to adapt what has worked for it to a new arena. Garth Chouteau, PopCap's PR director, sees great challenges and opportunities for expansion into the

"

Blending a social experience with game design is neither obvious nor easy, he cautions. "What aspects of a given game beyond high score do people want to communicate to their personal networks of contacts? Great shots, moves and replays; hardest-fought matches with particular mutual contacts; most achievements accomplished; prizes won? These and other aspects of our social-game offerings are still to be determined."

Everyone I spoke to emphasized that the social part of social gaming is the most important part of the equation. The games only exist to build or expand social capital.

"Even offline people assign values to interactions," explains Barber. "It's the difference between waving to somebody and lending them money. Online it's the difference between 'poking' someone on

Where the

Charles Forman, a game designer at OMGPOP, has no illusions about how original or durable his company's games are. "You come to the site because you have five minutes to waste. It's not about the content; it's about interaction with other people."

"On

This model has proven very successful, Forman says, with a lot of the money coming from gamers buying power-ups or cute accessories. "But they mostly buy them for other people," he notes with pleasure. "A lot of the micropayment purchases are birthday gifts or a bunch of guys trying to impress a girl." OMGPOP's games are head-to-head, not asynchronous like Playdom's or Zynga's role-playing games, or high-score-oriented like PopCap games. This means there is greater interaction between the players in real time, creating what Forman believes is a true social experience.

But even to a casual observer, the landscape seems barren of original design ideas.

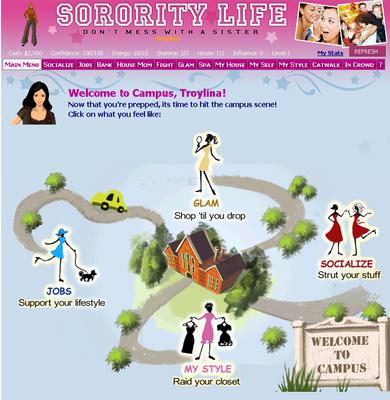

"You have to understand. This is still a very young space," says Meretzky. The veteran game designer is a vice president at Playdom, the maker of Mobster, Sorority Life and a half-dozen other social games available on

The imitation is hard to miss. Playdom's "Sorority Life" and Zynga's "Mafia Wars" could not have more radically different subject matter, but their gameplay is virtually identical (except for "Sorority Life's" mini-games, which include casual-game cliches like match-three). Both are role-playing games that let you complete tasks for monetary rewards. Repetition of a task leads to mastery and experience, and then you can unlock new tasks. You need to acquire new items and a larger circle of friends in order to get to the best content. For an experienced gamer, both titles appear to be only slightly more interactive Web versions of "Progress Quest": Just give it enough time and you will get to where you want to go.

The pressure to stick with a tried-and-true formula is obvious. A successful social RPG like "Mafia Wars" can get 4 million players a day -- only a few of whom need to actually click an ad or buy an item. The card, puzzle and word games that dominate these platforms can hit similar numbers. Developers and publishers, therefore, chase what has proven popular.

"Six months ago there were zero farm-themed games," says Steve Meretzky. "Now there are lots. Was there an untapped market for farming games? Probably not. But one was a hit, and people wanted a piece of that."

"If farm games are big, you need a farm game," says Brian Reynolds.

Meretzky cautions that you can't think about game design in the social gaming arena in quite the same way as you can in the traditional gaming space. "Success is determined by how you use the gameplay to make people want to involve their friends. Once, this was simply power based on the number of friends you had. But the state of the art is progressing very quickly. The demographics are changing, but the games are still very casual."

This design emphasis on mass socializing is what makes game design for the social space so unique. But OMGPOP's Charles Forman questions how much game design there even is. "The jury is still out on whether

It's worth keeping in mind Meretzky's reminder that these games are only in their early days. He notes that the asynchronous nature of his company's RPGs presents interesting challenges for designers. Many of the games integrate ways you can help your friends -- but since it's unlikely that you and your friends will be online at the same time, you never know if or when that help is coming.

Brian Reynolds is optimistic about the future of real game design in social gaming, mostly because -- as he sees it -- the hard work is already done. "They have the Web-based social stuff down, but not the gameplay. Now people like me can do a lot for this space. The social relationship thing is really hard to learn."

Reynolds thinks that a lot of traditional game design is missing from most social games. For example, he points to the "inverted pyramid of decision-making", where you begin with simple parts and then slowly build an elaborate system from player decisions. "The pyramid, of course, would be a lot narrower than something you would find in Civilization, but there's no reason you can't use that tool in social games."

Whether there is room for a greater variety of game design is a business question, too. A recent story by Christian Nutt in Gamasutra questioned the place of "fun" in a business environment seemingly obsessed with "virality" and developing metrics to measure everything. Everyone I spoke to emphasized that while the financial side to any industry is important, it should not be overstated.

"We're not a nonprofit," says Barber. "But revenue is (Zynga's) third priority at this point. First, we want to keep our users engaged; and second, we want to bring in new players. Honestly, I don't think we've even begun to optimize our revenue stream."

Charles Forman made it clear that on the game-design side, social gaming companies are not that different from traditional developers.

"Content development is an investment. Nothing is worse than investing in something original and then finding no one wants to play it." It's easy to track information on what works and what doesn't (and what pays and what doesn't), but traditional game publishers have done this for years. The scale of social gaming makes it different, it is argued, but the principle is not necessarily insidious.

Barber acknowledges that it is difficult to get traditional gamers and mainstream gaming media interested in social gaming. Few Web sites are devoted to covering it, and it's very unlikely that you'll find a long discussion of "Farmville" or "Farm Town" or "My Farm" in your favorite gaming forum. Social gaming is still in an early-Nintendo Wii phase: Because it targets such a broad audience, it is easy for the hardcore gaming population to dismiss the games as unserious, and the platform as unworthy of attention. The announcement that Reynolds was joining Zynga, for example, was met with more tears than curiosity. Why would he want to work on games like that?

The glass-half-full approach, of course, is to anticipate more frequent Brian Reynolds-designed games. It is inevitable that a well-designed game will eventually emerge. Like a new marshal riding into a Wild West town, top-tier design talent confers legitimacy on the space and may end up "civilizing" it.

Recently, EA's Soren Johnson made the case that the Web game may be the future of PC game design, especially on the strategy side. Just as single-player casual games had to go through endless repetition before the market was mature enough for a variety of designs and business models, social gaming is finding its way as a platform and style. OMGPOP's Forman is right; the jury is still out on whether established social networks are the best place for innovation, or gaming in general. But social gaming is growing, while the other parts of the market are shrinking -- and gamers shouldn't ignore it.