- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

Henry A. Kissinger

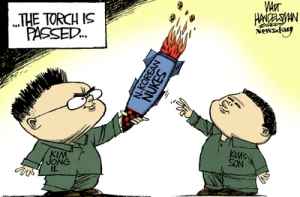

The American special representative for North Korea, Stephen Bosworth, returned from Pyongyang after unusually benign conversations. The North Korean government affirmed "the need to resume [six-power talks]" on the nuclear disarmament of the Korean peninsula. However, it added the proviso that the United States and Korea "needed to cooperate to narrow the remaining differences" before it would rejoin the established six-power diplomatic framework, from which it had walked out a year ago while abandoning all the undertakings it had made during those talks. In other words, Pyongyang seeks separate negotiations with the United States while keeping the other parties out of the diplomatic process, at least for a while.

North Korea's agenda links its denuclearization to the completion of a Korean peace treaty, a Northeast Asia security system, normalization of relations with the United States and removal of any threat against it -- presumably from whatever source. This is not an agenda lending itself to rapid resolution. A negotiation over a peace treaty, for example, would surely involve a controversy over the presence of U.S. forces in South Korea. The North Korean approach seems, above all, designed to gain time and to split the five other parties.

It is time to face realities. We are now in the 15th year during which America has sought to end North Korea's nuclear program through negotiations. These have been conducted in both two-party and six-party forums. The result was the same, whatever the framework. In their course, Pyongyang has mothballed its nuclear facilities twice. Each time it ended the moratorium unilaterally. Twice it has tested nuclear explosions and long-range missiles during recesses of negotiations: the first test series in

When the Obama administration took office, Pyongyang refused a visit by Bosworth and rejected a hint of direct contact with the secretary of state. Only after completing its most recent series of tests did Pyongyang move toward negotiations, but only with the United States. If there is no penalty for intransigence, deadlocks become the mechanisms for filling the time needed for further technological progress. Why should Pyongyang alter its conduct when, within weeks of the end of a test series, an American special representative appears in Pyongyang to explore the prospects of new negotiations? At a minimum, before any formal talks take place, North Korea should be required to return matters to where they were when it broke off talks, specifically, mothballing its plutonium production.

Pyongyang argues that its security concerns must be met first, that the principal threat to its security comes from America and that it therefore must gain special assurances from Washington before entering actual negotiations. But what bilateral assurances could possibly serve this purpose? Only a Northeast Asia security system could come close to creating an appropriate framework, and this requires the six-party forum.

Nor is Pyongyang so naive as to believe it could achieve security by threatening a nuclear strike at the United States. Far more likely, North Korea seeks recognition as a nuclear power so that it can intimidate South Korea and Japan, which have so far refrained from joining the proliferation process. It can also gain support by assisting weapons programs, as it has in Pakistan, and in Syria, for which it built a copy of its own plutonium plant. North Korea seems so on automatic pilot that even while Bosworth was in Pyongyang, a plane loaded with missile parts was dispatched to South Asia where it was intercepted in Bangkok. Pyongyang, in its more exuberant moments, may even see itself in a position to play off Beijing and Washington against each other.

Pyongyang knows that each of the other participants in the six-party talks has every interest in bringing the nuclear weapons threat to a rapid conclusion, while Pyongyang's own interest is to stall the negotiations for as long as possible. This is why bilateral U.S. talks with Pyongyang tend to undermine the unity of the remaining four. South Korea will resent peace talks in which North Korea is a party in a bilateral forum that excludes Seoul. It also strengthens Pyongyang's attempt to present itself as the genuine representative of Korean nationalism. Japan will not delegate its concerns regarding its citizens abducted by North Korea as forced labor to train North Korean intelligence personnel.

The position of China is more complex.

It has strongly condemned Pyongyang's nuclear testing. But it is more sensitive than its partners to the danger of destabilizing the political structure of North Korea. Great respect must be paid to Chinese views on a matter so close to its borders and directly affecting its interests. But in the end, a face-saving gesture for Pyongyang will be meaningful only as a brief transition to the six-power forum.

On North Korea and earlier on Iran, the protracted process of opening negotiations runs the risk of becoming a palliative for substance. The test, however, is substantive progress on the key issue: the elimination of a nuclear weapons capability in North Korea. In view of the continuing technological progress in Pyongyang, which claims to have added a nuclear enrichment facility to its plutonium program, time is of the essence. The catalogue for reciprocal security and economic assurances is well-established, and the United States should make its contribution to it -- short of accepting a definition of itself as a special threat. In the end, the greatest risk to Pyongyang is not foreign aggression but internal collapse caused by its excessive ambitions. No special reconnaissance is needed about Pyongyang's intentions when the six-party forum exists where they can be displayed. The famous dictum of Napoleon is apposite: "If you want to take Vienna, take Vienna."