- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Politics

By Elizabeth C. Economy & Adam Segal

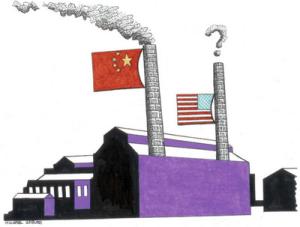

One of the things U.S. President Barack Obama's foreign policy team accomplished most quickly was the forging of a single line on China: more cooperation on more issues more often.

Calling on the United States and China to do more together has an undeniable logic.

Both Washington and Beijing are destined to fail if they attempt to confront the world's problems alone, and the current bilateral relationship is not getting the job done.

But elevating the bilateral relationship is not the solution.

It will raise expectations for a level of partnership that cannot be met and exacerbate the very real differences that exist between Washington and Beijing. The current lack of U.S.-Chinese cooperation does not stem from a failure on Washington's part to recognize how much China matters. It derives from mismatched interests, values, and capabilities.

The United States must accordingly resist the temptation to initiate a high-stakes bilateral dialogue and instead embrace a far more multilateral approach to China.

In other words, Obama should continue to work with China in order to address global problems, but he also needs to enlist the world to deal with the problems created by the rise of China.

One significant obstacle to effective U.S.-Chinese cooperation is the dramatically different view of sovereignty, sanctions, and the use of force that each country brings to the table.

Beijing's need for resources and export markets, along with its oft-repeated mantra of not mixing business with politics, clashes with the West's efforts to prevent human rights abuses and improve governance in the developing world.

In addition, China's authoritarian but decentralized political economy makes cooperation on more technical issues such as product safety and environmental protection difficult.

With actors inside of China often pursuing their own interests, Beijing is incapable of following through on its international obligations. Although the press, bloggers, and nongovernmental organizations are becoming increasingly assertive, they are unable to act consistently as a check on local officials due to censorship and political harassment.

Finally, there are serious differences between what the two countries want economically and when they want it.

Washington insists on currency reform, more open markets, and the protection of intellectual property rights. Beijing, by contrast, generally wants to be left alone to conduct its business as it sees fit. Even when China has engaged directly on economic issues--such as the protection of intellectual property rights--it has viewed its efforts in terms of change over decades, a timetable completely out of line with the United States' much greater expectations.

Although the United States needs to coordinate with China to respond to global challenges, elevating the bilateral relationship is more likely to lead to a quagmire than to a successful partnership. Washington must instead solicit the help of the rest of the world.

As a first step, the Obama administration should sit down with Japan, the EU, and other key allies to begin coordinating their policies toward China. Much of what the United States does, or is proposing to do, with China on the environment, human rights, and food and product safety is also being discussed or undertaken by Canada, the EU, Japan, and other states in Asia. Yet there is presently no coordination, which means these simultaneous efforts will be inefficient and may work at cross-purposes.

As the global economic crisis deepens, trade becomes an area ripe for multilateralism.

The United States has the opportunity to work with the many countries that are now running trade imbalances with China to push Beijing to reduce export subsidies and further open the domestic market. If approached multilaterally, these demands could be framed in the context of global, rather than bilateral, imbalances.

Despite insistent calls for a bilateral U.S.-Chinese effort to address climate change, cooperation would be managed best by involving other nations.

The United States and China are the two largest emitters of carbon dioxide, and each is using the other as an excuse for inaction.

And while the United States has some comparative advantages when it comes to training Chinese officials and designing some clean-energy technologies, there is a very real danger that Washington will raise expectations but fail to deliver, as has happened with past cooperative energy and environmental ventures.

Finally, Washington will need to look beyond its traditional allies to help enhance its leverage over Beijing.

On sensitive political issues, working with the same developing countries China purports to represent -- African countries on Darfur, island nations on climate change -- will be more effective in changing China's behavior than yet another call for action from Brussels or Tokyo.

Further elevating the U.S.-Chinese bilateral relationship without addressing the real differences in values and enforcement capacities between the two countries will lead nowhere -- except to the creation of more empty frameworks for dialogues and never-ending dialogues to establish more frameworks.

The time has come to acknowledge that although working with China sounds easy, it is not.

If the United States wants to move its relationship with China forward for the next 30 years, it needs the rest of the world on board.

Elizabeth C. Economy is C. V. Starr Senior Fellow and Director for Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. Adam Segal is Maurice R. Greenberg Senior Fellow for China Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Receive our political analysis by email by subscribing here

© Tribune Media Services, Inc