- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

By Joshua Kurlantzick

2018 was a brutal year, in many ways, for journalism, civil society activists, rights advocates, and democratic politicians throughout Southeast Asia.

Cambodia's government transformed from an autocratic regime where there was still some (minimal) space for opposition parties into a fully one-party regime. Thailand's junta continued to repress the population, attempting to control the run-up to elections in February 2019 that the junta hopes will result in a victory for pro-military parties and their allies. The Myanmar government continued to stonewall a real investigation into the alleged crimes against humanity in Rakhine State, despite significant international pressure to allow an investigation.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte appears to have moved on from using extrajudicial killings in his war on drugs to preparing to utilize extrajudicial killings in other ways. Last month, Duterte raised the idea of creating a new death squad to fight against communist rebels in the Philippines, for instance. And even in Indonesia, one of the freest states in the region, the Jokowi government has given off worrying signs of increasingly authoritarian tendencies. Jokowi has politicized top law enforcement posts, overseen criminal investigations of opponents, and shown other worrying signs, according to an analysis of his growing authoritarianism published in New Mandala by Tom Power, a PhD candidate at Australian National University. (Malaysia is a rare bright spot for rights and democracy in Southeast Asia this year -- in fact one of the few global bright spots for democracy in 2018.)

Perhaps nowhere has the increasing crackdown on rights and freedoms in Southeast Asia been more visible than in the area of press freedom. Of the journalists featured on Time magazine's series of covers of people of the year, three are from Southeast Asia. Two of those featured are Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, journalists for Reuters who have been jailed in Myanmar, essentially for investigative reporting into aspects of a massacre against the Rohingya. (They are officially charged with breaking the Official Secrets Act.) The two men have already been in jail for a year -- despite their trial being decried as a sham by rights organizations and prominent rights advocates -- and they face in total seven-year prison sentences.

Suu Kyi has defended their jailing, and the two reporters' time in prison is emblematic of Myanmar's worsening climate for independent journalism, even under Suu Kyi's government. As the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has noted, three other Myanmar journalists were arrested in October, and overall the Official Secrets Act, defamation charges, and physical threats are chilling the climate for reporting in the country.

The climate for press freedom is poor in Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam as well. For example, in Cambodia, one of the leading print outlets, the Cambodia Daily, closed in 2017, reportedly under pressure from the Hun Sen government. Another leading independent outlet, the Phnom Penh Post, was sold to a new owner in 2018, amid worries that the new management would curb critical and investigative reporting. Many Phnom Penh Post staff members quit. Meanwhile, in Vietnam the government continued to aggressively shut down independent bloggers and writers, and Thailand's junta has continued to harshly repress reporters and editors, such as reportedly pushing for the sacking of the top editor of the Bangkok Post, a leading Thailand newspaper, for his critical coverage of the military regime.

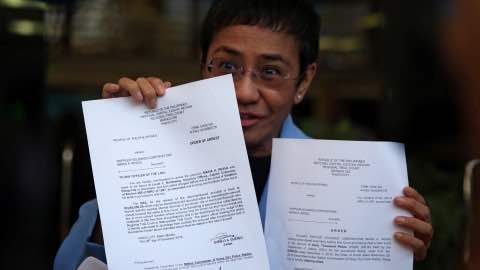

Maria Ressa, the head of Rappler, one of the Philippines' toughest and most groundbreaking news sites, is probably the best-known case of press freedom under attack in Southeast Asia. Before becoming the CEO of Rappler, Ressa had amassed a broad range of experience, including working for two decades for CNN, for whom she covered everything from the rise of Islamist terror networks in Southeast Asia to the post-Marcos era in the Philippines. She has received a wide range of awards for her work, including an Emmy nomination and an Overseas Press Club award.

Like many authoritarian-leaning populists, Duterte aggressively demonizes the media, and Rappler in particular seems to infuriate him, with its hard-hitting, deep-digging style. The Duterte administration seems determined to put Rappler out of business. In early 2018, the Philippine SEC announced that it was revoking Rappler's license. The media organization fought, and continued operating, but it was then accused of libel by the Philippine national bureau of investigation, and then was hit with tax evasion charges by the Philippine tax agency.

Ressa herself also was charged with tax evasion, only a few days after she got a press freedom award from CPJ. She and the media outlet deny the charges, and noted how quickly the Philippine government had moved to file charges, seemingly without considering all motions and evidence. The case is now proceeding -- but the climate for press freedom in the Philippines, which long combined tough investigative reporting with one of the most dangerous environments for journalists in the world, looks like it will only get grimmer in 2019.

Photo: Maria Ressa, an executive of online news platform Rappler, shows her arrest warrant and release order after posting bail for tax evasion charges at Regional Trial Court Branch 265 in Pasig City, Metro Manila, in Philippines. Eloisa Lopez/Reuters

Article: Courtesy Council on Foreign Relations.

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

"Press Freedom Under Assault in Southeast Asia"