- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Politics

by Bill Press

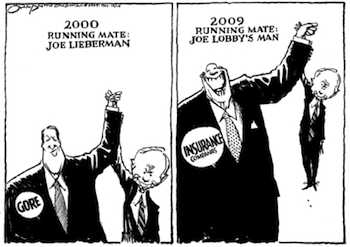

The legendary Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield used to caution fellow senators: "Never question another man's motives, question his judgment." Maybe so, but it's hard not to question the judgment, motives, and sanity of Joe Lieberman, who has single-handedly derailed any meaningful health care reform legislation.

For years, Lieberman's been a strong advocate of universal health care.

Campaigning for vice-president in 2000, he first proposed resolving the plight of the uninsured by allowing them to buy into

Yet when that very same plan -- call it "Lieberman's Plan" -- was added to

No doubt, part of it is just pure revenge. Ever since being rejected by Connecticut Democrats in the 2006 primary, and getting re-elected as an Independent, Lieberman's been all about payback. That's why he endorsed John McCain for president, campaigned nonstop for him, spoke to the

Lieberman never cared about them, anyway.

Joe Lieberman only cares about Joe Lieberman -- and the Connecticut-based insurance companies that have financed his political career. He's taken more than

Whatever his motives, Lieberman has worn out his welcome among Senate Democrats. They should have thrown him out of the Senate Democratic Caucus last year. They didn't. So now's the time. Toss Lieberman out of the caucus. Strip him of his chairmanship of the Homeland Security Committee. Then tell Lieberman that all legislation bearing his name has been put on permanent hold, and all funds earmarked for Connecticut have been re-assigned to Mississippi. He and his constituents must know there's a price to pay for disloyalty.

Next priority: Kill the filibuster! Or at least modify it so it can't be used as a one-man assassination squad.

The filibuster is hardly new. It dates back to Cato the Younger, whose long-winded speeches would keep the Roman Senate in session until nightfall, past the deadline for completion of business, and thereby killing any legislation he opposed. Until recently, U.S. senators used the filibuster much the same way: to defeat a bill by talking it to death. The record is still held by South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond who filibustered for 24 hours and 18 minutes against the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

In 1975, an important change was made: the number of votes needed to end a filibuster was reduced from 67 to 60. Unfortunately, two other less welcome changes were made. Senate Rule 22 now permits filibusters in which actual continuous floor speeches are not required. And members of both parties have extended the filibuster to nontraditional uses.

In 2005, when Democrats vowed to filibuster several judicial nominees of President George W. Bush, Republican Leader Bill Frist threatened a "nuclear option," declaring such use of the filibuster unconstitutional. Later, with Democrats in charge, Republicans demanded a filibuster as a prerequisite to any vote. Meaning: even if you have the support of 51 senators necessary to pass a bill, you can't schedule a vote unless you first deliver 60 senators. That's how just one man can now prevent senators from doing their job. It's in the interest of both parties to end that potential for abuse, once and for all.

Ironically, the last attempt to fix the filibuster was made in 1995 by Sen. Tom Harkin. Harkin's measure would, over time, have gradually reduced the number of votes necessary to end a filibuster. It was a sensible proposal. Here's the kicker: His co-sponsor was Joe Lieberman.

AMERICAN POLITICS

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Receive our political analysis by email by subscribing here

© Tribune Media Services, Inc