- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Politics

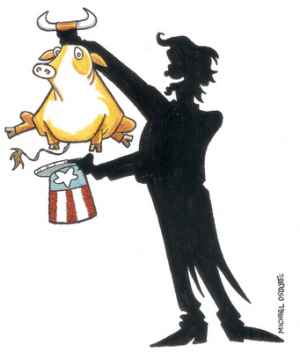

by Ian Bremmer & Sean West

It's no secret that politics affects markets.

Every move the government makes can have micro-level effects on individual stocks; President Barack Obama's proposal to restructure student-loan incentives caused Sallie Mae's stock price to halve in 48 hours in late February.

But in response to a financial crisis or economic downturn, political risk impacts markets much more broadly than just isolated policies and individual stocks.

It is easy to note in retrospect from last October until mid-May that the Dow Jones Industrial Average experienced at least a half-dozen significant inflection points either on the day of or as details leaked about political events like major votes in Congress or policy speeches.

The challenge is to anticipate and understand how and in what ways broad government intervention creates macro and micro political risks for investors and corporations.

The biggest danger in doing so is to view political players through a static ideological lens, rather than a nuanced collection of assumptions that are consistently updated in the context of broader government efforts and timeliness.

Washington Post columnist George Will last month extrapolated from the sweet deal labor received related to Chrysler that the "administration's central activity -- the political allocation of wealth and opportunity -- is not merely susceptible to corruption, it is corruption."

This position implies that simply by knowing the administration's political favorites, it is possible to anticipate who will get wealth and opportunity.

This would make political risk straightforward: When in conflict with big business and big finance, it would be expected that workers, consumers and lower- and middle-income taxpayers should always win.

This would have been a dangerous anticipatory framework to forecast the government's intervention given how market-friendly the administration has been in dishing out non-auto-related aspects of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP).

On big-ticket items, the Obama administration has been quite market-friendly in its proposals.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 7 percent the day the government's Public Private Investment Program (PPIP) was revealed to potentially saddle taxpayers with nearly all downside risk while providing market players with possibly massive upside.

Regardless of how economically (in)efficient the package's construction is, the stimulus passed in February provides business with hundreds of billions of dollars of potential revenue in hopes of jumpstarting the broader economy.

Alone, these two programs represent over a trillion dollars of friendly firepower.

Contrary to Will's takeaway, the administration's consistently market-friendly proposals might actually imply an equally dangerous small macropolitical risk because the government looks to be supporting business and finance.

From that assumption, it would seem like an effective strategy to only focus then on micro-level risks related to individual firms -- like Chrysler -- and ignore the broader risks brewing in the system.

In that case, market enthusiasm for the unveiling of PPIP -- which was based on the assumption that PPIP would be implemented as Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner presented it would be -- might have been justified. But ignoring implementation risk and focusing only on micro-level risks would also be an ineffective strategy, because a swarm of micro-risks can delay or disrupt recovery just as easily as an unfriendly government.

Instead, it is necessary to understand the government's actions and programs in context.

The administration needs to present a good deal for financial players upfront, because it cannot actually shepherd the economy and the financial sector toward recovery without their participation.

It also needs to set a high bar of market support, so that as Congress chips away at its subsidies and "giveaways" resulting policy will still be enticing enough to get participation. Individual members of Congress need to both appear as guardians of the taxpayer dollar and as protectors of the interests that keep them in power. The interaction of these forces and incentives creates a host of political risks that belie a singular characterization.

Micro-risks are playing out in financial and corporate decision-making related to participation in the government's programs. There is clearly risk that PPIP rules may change mid-process. Indeed, Congress last week mandated that all participants acknowledge a fiduciary responsibility not just to investors but also to the general public and calibrated a somewhat intrusive level of disclosure for participants.

Some firms -- like BlackRock -- have made a clear choice that the risks of strings and increased public scrutiny are well worth the payoff of playing ball with government. But despite Treasury's best efforts to wall off participants from executive compensation restrictions, some firms, like JP Morgan, have made it clear that they'd rather leave subsidized money on the table than subject themselves to further uncertainty related to government intrusion.

And while PPIP does not need uniform participation across the financial sector to make progress, the macro-risk is that as implemented its program is not attractive to enough players to get the market for toxic assets working again. Indeed, rumors emerging last week that half the program may be delayed or cancelled due to lack of private sector interest demonstrates how real this risk is.

Similarly, corporations are beginning to demonstrate awareness of the firm-level risks related to participating in the government's stimulus program. There are a handful of programs that were controversial when inserted in the package, and the risk that opposing politicians closely scrutinize their performance on such contracts is real.

Couple the politically charged nature of the stimulus with the high levels of transparency the Obama administration wants to implement, and it's obvious that there will be a readily available index for those who want to cry corporate welfare.

Certainly this risk won't scare away infrastructure firms and others who have large pools of money to potentially earn. But it could slow down progress on more marginal programs where performers would rather skip relatively small pieces of work than take on reputational risks. The macro-risk here is that these individual firm choices aggregate to slowing down the already priced-in stimulus.

If these programs take hold and the system stabilizes, the risk environment changes.

Then both sides of Pennsylvania Avenue will need to figure out how to extricate the government from intervention, contain inflation and prevent the risk of the U.S. losing its AAA credit rating.

That this could include a series of fees on the financial sector to recoup any rescue costs funded by taxpayers, as well as slashing otherwise lucrative spending programs, clarifies that political risk remains even amid recovery.

However, if the system does not stabilize, the political risks will surely be much greater.

In that case, the administration will try to deflect blame for wasting time and money onto the financial sector and corporations at the same time that it gets much more aggressive in its intervention.

That's when things could really get ugly.

Ian Bremmer is president of Eurasia Group, a global political-risk consultancy. He is co-author, with Preston Keat, of the book "The Fat Tail: The Power of Political Knowledge in an Uncertain World." Sean West is a Washington-based analyst with Eurasia Group.

AMERICAN POLITICS

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Receive our political analysis by email by subscribing here

© Tribune Media Services, Inc