- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- VIDEOS

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Economy

by Liz Wolgemuth

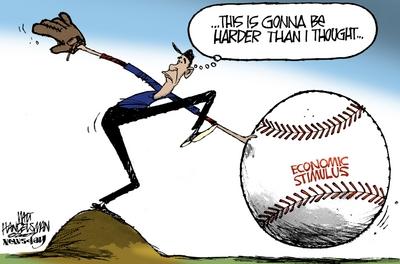

First economic stimulus was supposed to help with employment. What could a second economic stimulus package do better?

While murmured calls for a new stimulus package have not quite transformed into a movement, the din is loud enough that the White House has issued multiple responses that basically amount to "no, not yet."

But Americans are stumbling through a job market that is overwhelmed with supply, stripped of security, and skimmed of hours and benefits, and the unemployment rate has already climbed much higher than officials had forecast.

So, the real question is, what could a second Obama administration stimulus do that the first one couldn't?

To answer that, it's necessary to know how the first $787 billion package has disappointed.

An overly optimistic forecast: The goal of the first Obama stimulus was job preservation and creation, through instruments such as infrastructure spending and expanded jobless benefits.

In a report the administration used to make its case for the stimulus, White House economists forecast unemployment rates cresting at 8 and 9 percent -- with and without the stimulus package, respectively. But they included a brief endnote: "Forecasts of the unemployment rate without the recovery plan vary substantially. Some private forecasters anticipate unemployment rates as high as 11 percent in the absence of action."

Today, everyone knows they would have done better to have used the most pessimistic forecasts in their calculations.

The unemployment rate has hit 9.5 percent with the stimulus, and employers are still cutting jobs. Vice President Joe Biden has said the administration "misread how bad the economy was."

Where the first Obama stimulus package went wrong

While the successes or failures of the first stimulus package may never be objectively measurable, critics charge that it has parceled out money too slowly and included projects of debatable merit when it comes to job creation.

Harvard University economist and former Reagan adviser Martin Feldstein maintains that the money could have done more.

"In the first stimulus, only about 25 percent was government spending," Feldstein says.

"The other 75 percent [was] transfers to individuals, temporary tax cuts, or transfers to government. These had much less impact on GDP. If the nearly $800 billion dollars had been spent effectively, it would have done much more."

Economist Paul Krugman has long insisted the first Obama economic stimulus was simply not large enough to compensate for the drop in gross domestic product.

Dean Baker, codirector of the liberal Center for Economic Policy Research, shares that view. "I think the big problem was size," Baker says. "I don't doubt for a moment we'd be in a worse situation [without it] &ellips; but the order of magnitude just wasn't there."

What another economic stimulus package could look like:

Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell, who is chairman of the National Governors Association, told Congress last week that he would like to see a second stimulus devoted entirely to infrastructure. "It's what produces jobs and produces orders for factories, American factories," Rendell said. Obama economic adviser Laura Tyson has also said a new stimulus would be best focused on infrastructure.

Others would pack projects into a second package that were dropped from the first. But Baker is skeptical that a package of the previous stimulus's leftovers would be particularly effective.

Instead, he suggests immediate relief to strapped state and local governments and more creative moves, such as subsidies to lower the cost of mass-transit rides, which would increase use of public transportation and put cash in the hands of riders, who tend to be disproportionately lower-income (and more likely to spend their relief immediately). Also, a tax credit for employers who give paid time off to existing employees might help beef up hiring, as employers increase their payrolls to compensate for employees working fewer hours.

The downside of a second economic stimulus package

The Congressional Budget Office forecasts a $1.85 trillion deficit for the fiscal year -- a figure that gives many economists (and Americans) pause.

Feldstein says he is not in favor of a second stimulus because it would boost the national debt, increasing the burden on taxpayers and possibly pushing long-term interest rates higher.

Higher interest rates would constrain business expansion and economic growth -- not exactly the goal of a stimulus. Paul Krugman, for his part, is suspect of the position that a second stimulus would create a real debt problem for the country. "Does anyone really think that, say, another $500 billion in borrowing would be the straw that breaks the camel's back?" he says.

The most obvious argument against a second stimulus is the fact that the vast bulk of the $787 billion stimulus has still not been spent.

For example, as of Thursday morning, the Agency for International Development had $5.3 million available and about $400,000 paid out so far.

The Department of Energy had $7.9 billion available and less than $300 million paid out.

The Department of Transportation had about $21 billion available and a bit less than $700 million paid out.

Stimulus spending is expected to speed up over the summer. And infrastructure spending was never expected to be an immediate job creator because "shovel-ready" projects are rare; it takes time for most projects to ramp up.

President Obama insists it's premature to talk about another stimulus, and there seems a case to be made for some patience.

© PAUL A. SAMUELSON; (TM) TRIBUNE MEDIA SERVICES, INC.

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMY | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Would a Second Stimulus Create Jobs?; The first one was supposed to help with employment. What could a second do better?