- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Politics

by Kent Garber

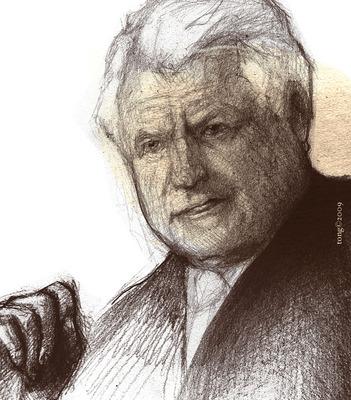

Senator Ted Kennedy (© Paul Tong)

Ted Kennedy's death could change the tone and direction of the healthcare reform debate

Senator Ted Kennedy was out of sight this summer, fighting the brain cancer that finally claimed his life, but up until his last days he was still at work, following C-SPAN's healthcare reform coverage and calling his Washington colleagues.

Earlier this month, he phoned Connecticut Sen. Chris Dodd, a close friend, to offer advice. "He was just as courageous as he could be," Dodd said last Wednesday, the morning after Kennedy's death. "Less than two weeks ago, when he called, it was like he had never been sick. He was down with the details on how to deal with costs -- literally, two weeks ago."

Though Kennedy is gone, the cause of his career -- universal health coverage -- is simmering at the forefront of national politics,

much as it was in the early 1970s and again in the 1990s.

Kennedy was the country's dominant healthcare figure for much of his career

Even after his cancer diagnosis forced him to leave Washington last year, he ranked as the sixth-most-powerful

healthcare player in the country, according to a survey by the trade magazine

Baucus says the Gang of Six is working on a healthcare bill that will win bipartisan support. But amid August's wild town halls and the new concerns among liberals that a public health insurance option will be dropped from the bill, many Democrats have grown restless with its promises.

Some, like New York Sen. Chuck Schumer, say that if Democrats want to get something done, they are going to have to do it alone. But Kennedy's death may make that more difficult. Democrats have only 59 votes in the

Had Kennedy been present, experts say, this summer's debate might have been more civil and reasoned, not just because of the deep respect he commanded from members of both parties but also because of his ability to talk in compelling and clear terms about healthcare. "We have been lacking articulation," says

Yet Marmor and others also say that Kennedy, who remained a life-long idealist on large issues like national healthcare insurance, could only have done so much, given the partisan nature of the debate. "There is no doubt he would have been the most eloquent voice there could be for the cause of universal health insurance," says Jonathan Oberlander, a health policy expert and professor at the

Perhaps the biggest impact of Kennedy's absence has yet to be felt. Assuming that a bill does pass the

AMERICAN POLITICS

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Receive our political analysis by email by subscribing here

© Tribune Media Services, Inc