- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

Dan Gilgoff

When Orthodox Jews met with top

But the Jewish delegation also based its case for a climate change bill, which cleared the House earlier this year, on another premise: the Bible. "We are getting ready to read Genesis and the creation story in our synagogues in a few weeks," Diament says. "Our responsibility to tend the garden is part of our understanding of the Torah and of our worship." Indeed, some Jews have begun referring to their green activism as "creation care," a term coined by environmentally inclined evangelical Christians.

As environmental interests begin pressing the

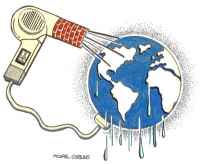

At a time when many senators are skittish about adopting the House climate bill's cap-and-trade provision because of fears it could further slow the economy, religious activists may prove crucial to building support, or at least dampening opposition, among important religious constituencies. Religious conservatives, for instance, generally oppose more government regulation. And many African-Americans, among the most religious demographic groups in the country, worry about cap-and-trade's impact on manufacturing jobs. Faith-based environmentalists have responded to such doubts with a moral case that climate change will disproportionally affect the world's poor by causing food shortages, drought, and coastal flooding. "The faith community talks about climate legislation differently than scientists or environmentalists," says Cassandra Carmichael, director of the Washington office of the

With the healthcare debate sucking up most of the oxygen in Washington, a climate bill might not have a chance in the

In the House, religious activists helped to narrowly pass a climate bill in June. A group called the American Values Network, founded by the religious outreach director for Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign, Burns Strider, bought Christian radio ads promoting the bill in conservative congressional districts. The progressive group Faith in Public Life funded polling that showed most evangelicals and Catholics support efforts to combat climate change. Religious lobbyists, meanwhile, won a provision in the House bill guaranteeing that houses of worship are eligible for federal subsidies for retrofitting energy-inefficient buildings.

The stepped-up environmental efforts of religious groups in Washington have paralleled a grass-roots effort among religious Americans to green their congregations. An ecumenical group called GreenFaith recently launched a program to certify green houses of worship. Earlier this month, the

Though some religious activists were present at the environmental movement's inception, the greening of American faith took off in the past decade. "The work first emerged among mainline Protestant and liberal Jews and Catholics," says the Rev. Fletcher Harper, executive director of GreenFaith. "They were looking to reassert a religious voice for the common good and social justice after 30 years of a conservative evangelical take on public issues." Some evangelicals have since joined the movement, with leaders of the

At the same time, religion remains a dividing line in public opinion on the environment. Despite polling by progressive groups on support for climate legislation, a recent Pew survey found that just a third of white evangelicals believe global warming is caused by humans. And only 39 percent of black Protestants accept the evidence for human-caused climate change. The group most convinced that humans are to blame? Those unaffiliated with any religious tradition.

The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable Available at Amazon.com (Click Here)

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Religious Groups Push for Climate Change Legislation