- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

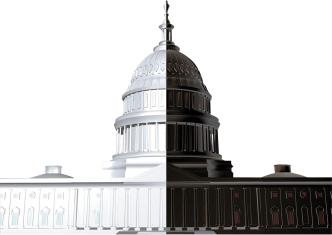

Not too long ago, Barack Obama would have found when he moved his family to Washington that his daughters couldn't attend the same schools white children could. They couldn't try on clothes or shoes at most local department stores, or eat at downtown lunch counters. Or see a play at the National Theatre or a movie just a block or two from the White House.

If a family pet died, it would have to be buried at a blacks-only cemetery.

"The owner stated that he assumed the dogs would not object, but he was afraid his white customers would," said a 1948 report on "Segregation in Washington."

Washington was largely a segregated city until the mid-1950s, a place where new students at Howard University were "briefed on what we could and couldn't do," recalled Russell Adams, now a professor emeritus of Afro-American Studies. "If you go downtown, don't try to eat," he said. "And don't try to buy stuff you didn't need, like shoes."

The major reason for the segregation was less geography than politics and custom. The city was ruled by Congress, and the key committee chairman or members were often white Southerners who boasted back home about their ability to keep the races separate. Sen. Theodore Bilbo, D Miss., a member of the Ku Klux Klan and the author of "Take Your Choice, Segregation or Mongrelization," headed the District of Columbia panel from 1945 to 1947.

Washington didn't have the widespread Jim Crow laws that ruled much of the Deep South; in fact, when the District briefly had home rule after the Civil War, laws gave blacks equal rights in public places. But the laws were forgotten and the city "operated as if there were Jim Crow laws," said Jane Freundel Levey, a historian for Cultural Tourism DC.

Blacks could get served at lunch counters, but they had to stand and eat. At the leading department stores, clerks "turn their backs at the approach of a Negro," the 1948 segregation report found. Most downtown hotels wouldn't rent rooms to blacks.

Some laws and rules separating blacks and whites were on the books. Schools were segregated. Segregation of federal offices — as well as restrooms and cafeterias — became widespread during the Woodrow Wilson administration, starting in 1913. In some post offices, partitions were erected to keep the races apart at work.

Housing covenants barred blacks from many neighborhoods, often squeezing them into substandard housing. A 1948 survey found that black families were nine times as likely as whites to live in a home needing major repairs, four times as likely to lack a flushing toilet and 11 times as likely to lack running water.

The Washington Real Estate Board Code of Ethics in 1948 put its view in stark terms: "No property in a white section should ever be sold, rented, advertised or offered to colored people." The Supreme Court that year declared such restrictive covenants unenforceable.

The barriers began to break down in the years after World War II, but slowly Actors' Equity pressured its members not to perform at segregated venues, such as the city's historic National Theatre.

"We state now to the National Theatre — and to a public which is looking to us to do what is just and humanitarian — that unless the situation is remedied, we will be forced to forbid our members to play there," the group, which represents thousands of actors and stage managers, announced in 1947.

The National Theatre, the city's premier live stage, closed in 1948 rather than integrate and showed movies instead. It reopened as a live theater four years later, under new owners who were willing to desegregate.

Up the street, however, blacks still couldn't go to many movie houses. First run films were screened in a strip of theaters along or adjacent to F Street, then the city's major commercial street, while theaters on U Street, the heart of the black community's commercial district, showed the same films to black audiences.

Many hotels would welcome blacks only if they were from another country.

"Our visitor's best chance (to get a hotel room) would be to wrap a turban around his head and register under some foreign name," said the 1948 segregation report. "This maneuver was successfully employed not long ago at one of the capital's most fashionable hotels by an enterprising American Negro who wanted to test the advantages of being a foreigner."

Things began to change in 1950, when 86-year-old Mary Church Terrell, a civil rights activist, tried to get served in Thompson's Cafeteria on 14th Street, about two blocks from the White House.

Blacks weren't allowed to sit and eat at most downtown lunch counters and cafeterias. In an affidavit, Terrell recalled her experience at Thompson's: "The manager told us that we could not be served in the restaurant because we were colored," she said, and along with three friends she left the restaurant and went to court. She targeted other restaurants, and in June 1953, Terrell won a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that segregated eating places in Washington were unconstitutional because the "lost laws" of the Reconstruction era were still in force.

Still, blacks were often made to feel unwelcome.

Carolivia Herron remembered going to Woolworth's lunch counter as a little girl, and the server immediately asked her if she wanted some watermelon. No, Herron replied, she wanted a grilled cheese sandwich.

Change came slowly. A black woman who wanted to try on a hat in a department store would be given a hairnet first; whites wouldn't. Blacks weren't allowed in fitting rooms and usually couldn't try on shoes.

Blacks and whites attended separate, and supposedly equal, schools until the Supreme Court's May 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Patricia Tyson went to the all-black four-room Military Road School, five miles from the White House.

Teachers would signal the start of class by ringing a handbell, but students were in awe of what Tyson recalled was an "electric bell" up the road at the white school.

The racial barriers gradually collapsed, though two glaring exceptions remained.

Glen Echo Park was the region's premier amusement park, where people could take the long streetcar ride on a hot summer day, swim in the Crystal Pool and dance the night away. Blacks were excluded until 1961.

Sports stadiums weren't officially segregated, and baseball's Washington Senators got its first black player in 1954, seven years after the sport was integrated. The owner, though, was seen as cool to black players.

The Senators moved to Minnesota for the 1961 season, and in 1978, owner Calvin Griffith reportedly told a local Lions Club he chose that location "when we found out that you only had 15,000 blacks here." And, he said, "We came here because you've got good, hard-working white people here."

Football's Washington Redskins didn't have a black player until 1962, and the team's fight song, "Hail to the Redskins," included a line urging the players to "fight for old Dixie."

Today, fans are urged to "fight for old D.C."

Black Americans in Public Office

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice

First black woman to hold the office; national security adviser under President George W. Bush; advised George H.W. Bush on Soviet Union.

Army General and Secretary of State Colin Powell

Highest ranking black officer in U.S. history; first black secretary of state; chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff during Persian Gulf War

United Nations diplomat Ralph Bunche

First black awarded Nobel Peace Prize, in 1950 for having mediated Arab-Israeli truce, and first to head a U.S. State Department division

Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall

Supreme Court's first black justice, 1967-1991; as an NAACP lawyer, won Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the 1954 Supreme Court case that overturned “separate but equal” schools.

Rep. Shirley Chisholm, D-N.Y.

First female black presidential candidate, in 1972; first black woman in House of Representatives

Rep. Barbara Jordan, D-Texas

First black elected to House of Representatives from South since Reconstruction; member of committee that held 1974 Watergate hearings

Sen. Hiram Revels, R-Miss.

First black U.S. senator, elected in 1870 during South's Reconstruction

Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., D-N.Y.

Lone voice of black protest in House of Representatives for years; elected in 1945 by Harlem district

Sen. Edward Brooke, R-Mass.

First black elected to the Senate by popular vote; served in the Senate 1967-1979; awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2004 Secretary of Housing and Urban Development

Robert C. Weaver

Nation's first black cabinet member, serving under President Lyndon Johnson 1966-1968