- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Asia Current Events

by Henry A. Kissinger

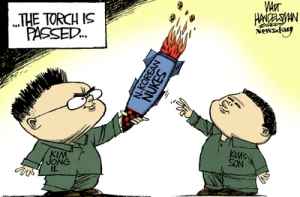

North Korea's Nuclear Challenge

The Obama administration had dealt publicly with the North Korean challenge in an understated, almost leisurely, manner.

Emphasizing continued reliance on multilateral diplomacy, it had invited Pyongyang to return to the conference table, even while North Korea threatens military action and tests nuclear weapons and the missiles to deliver them -- in the face of a declaration by all the major world powers that such actions are "unacceptable."

The challenge goes far beyond the regional security issue.

For America, it involves relations with an emerging superpower (China); relations with a re-emerging Russia; relations with key U.S. allies (Japan and South Korea); and a major escalation in the threat of proliferation to non-state parties.

The resumption of nuclear and missile testing by North Korea represents an abrupt reversal of a negotiating process that has been going, with only brief interruptions, for nearly two decades.

Since 2004, six-party talks in Beijing included all the countries (North and South Korea, China, Russia, Japan and the United States) directly threatened by North Korean missiles and nuclear weapons. For a while, it was argued that bilateral negotiations between the United States and North Korea would prove more effective.

[ Related: North Korea's Nuclear Ticket to Survival | Time to Test North Korea - Nuclear Weapons | Today, North Korea; Tomorrow, Iran | Israel's Cuban Missile Crisis All the Time ]

That debate has become largely academic.

Both approaches were pursued; both contributed to the stalemate inherited by the Obama administration. The six-power forum produced a framework agreement in February 2007 in which North Korea would abandon its nuclear-weapons program in return for a series of agreed reciprocal steps of diplomatic recognition and legitimization.

The implementation that followed of the agreement was largely negotiated between the U.S. and North Korea in a so-called two-power forum. Some progress was made: for example, the mothballing of Pyongyang's plutonium-producing plant in return for American political concessions, such as removing North Korea from the list designating states supporting terrorism. The United States pursued the two-power diplomacy implementation with such single-minded intensity as to bring about a near-crisis in our relations with Japan and South Korea, which complained of being marginalized.

I favored negotiations with Pyongyang and have occasionally participated in Track II dialogue with Korean officials outside formal channels. But with North Korea kicking over all previous agreements repeatedly, the time has come that process has overwhelmed substance. The ultimate test of the Korean diplomacy always had to be the elimination of North Korea's stockpile of fissionable material and nuclear weapons. But those were growing while the negotiations were proceeding at their stately pace. The negotiating process thereby ran the risk of legitimizing North Korea's nuclear program by enabling Pyongyang to establish a fait accompli by means of diplomacy. That point is fast approaching if it has not already been reached.

The Obama administration gave North Korea every opportunity to accelerate the negotiating process. While on a visit to Beijing, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton hinted that she was seriously considering a visit to Pyongyang. Stephen Bosworth, a distinguished scholar and moderate diplomat, was appointed principal negotiator.

These overtures were vituperatively rejected. Pyongyang used the change of American administration to signal a major shift in course. Bosworth was rebuffed while on a visit to the region. Refusing to return to the negotiating table, Pyongyang has also revoked all the concessions it had previously made. It has restarted its nuclear reprocessing plant and conducted another nuclear weapons test.

Many explanations have been advanced for the brazenness of North Korean tactics, such as a domestic struggle for succession to the clearly ailing "Dear Leader" Kim Jong-il -- though it is less clear who the factions are. But the only partially rational explanation is that North Korea's leaders have recognized that no matter how conciliatory United States diplomacy, it would in the next phase demand the destruction of North Korea's existing weapons capability.

Pyongyang's leaders have obviously decided to reject this outcome in the most absolute and confrontational manner. They must have concluded that no degree of political recognition could compensate for abandoning the signal (and probably sole) achievement of their rule, for which they have obliged their population to accept a form of oppression and exploitation unprecedented even in this period of totalitarianism. They may well calculate that weathering a period of protest is their ticket to emerging as a de facto nuclear power.

Hence the issue is no longer what forum should be used for negotiations but what their purpose is to be. The minimum precondition for a resumption of either of the existing forums would be that Pyongyang restore the previously implemented agreements that it has recently abrogated -- especially the mothballing of the plutonium separation plant. But that is not enough.

However the next diplomatic phase is conducted, the United States needs to enter it with the recognition that there is no longer any middle ground between the abandonment of the North Korean program and the status quo. Any policy that does not do away with North Korea's nuclear military capability, in effect, acquiesces in its continuation. A program of marginal additional sanctions followed by another protracted period of give-and-take would have that practical consequence.

The North Korean challenge thus confronts the United States with two basic options:

(a) to accept tacitly or openly that the North Korean nuclear program is beyond the point where it can be reversed and to seek to cap it and proscribe any proliferating activities beyond North Korea's borders;

(b) to attempt to end the North Korean nuclear program by a maximum deployment of pressures, which requires the active participation of Korea's neighbors, especially China.

Acceptance of the North Korean nuclear program would fly in the face of American foreign policy since we shepherded the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty through the international community in 1967, as well as of the policy put forward by President Obama only two months ago in a seminal speech in Prague. Acquiescence in a North Korean nuclear program would undermine prospects of the proposed negotiations with Iran. If the North Korean methods practiced during the Korean negotiations become a model for negotiations on Mideast nuclear programs, a chaotic world will beckon.

De facto acquiescence in a North Korean nuclear program would require a reconsideration of current U.S. strategic planning. More emphasis would need to be given to missile defense. It would be essential to redesign the American deterrent strategy in a world of multiple nuclear powers -- a challenge unprecedented in our experience. The enhanced role of non-state actors with respect to terrorism would have to be addressed. The concepts of deterrence against state actors are familiar; they have little or no relevance to non-state actors operating by stealth and difficult to identify.

A new argument in favor of acquiescence in North Korea's nuclear program has recently made its appearance. It contends that Pyongyang's conduct is really a hidden cry for assistance against Chinese domination and thus deserves support rather than opprobrium. But turning North Korea into a ward of the United States is neither feasible nor acceptable to the countries whose support for a solution of the North Korean nuclear issue is imperative.

No long-term solution of the Korean nuclear problem is sustainable without the key players of Northeast Asia, and that means China, South Korea, the United States and Japan, with an important role for Russia as well. A wise diplomacy will move urgently to assemble the incentives and pressures to bring about the elimination of nuclear weapons and stockpiles from North Korea. It is not enough to demand unstated pressures from other affected countries, especially China. A concept for the political evolution of Northeast Asia is urgently needed.

Too much of the commentary on the current crisis has concerned the deus ex machina of Chinese pressures on North Korea and complaints that Beijing has not implemented its full arsenal of possibilities. But for China, the issue is not so much a negotiating position as concern about its consequences. If the Pyongyang regime is destabilized, the future of Northeast Asia would then have to be settled by deeply concerned parties amidst a fast-moving crisis. They need to know the American attitude and clarify their own for that contingency.

China faces challenges perhaps even more complex than America's. If present trends continue, and if North Korea manages to maintain its nuclear capability through the inability of the parties to bring matters to a head, the proliferation of nuclear weapons throughout Northeast Asia and the Middle East becomes probable. China will then face the prospect of nuclear weapons in all surrounding Asian states and an unmanageable nuclear-armed regime in Pyongyang. But if China exercises the full panoply of its pressures without an accord with America and an understanding with the other parties, it has reason to fear chaos along its borders at or close to the traditional invasion routes of China. A sensitive, thoughtful dialogue with China, rather than peremptory demands, is essential.

The outcome of such a dialogue is difficult to predict, but it cannot be managed unless America clarifies its own purposes to itself. Some public statements imply the U.S. will try to deal with specific North Korean threats rather than eliminate the capability to carry them out. They leave open with what determination Washington will pursue the elimination of the existing stockpile of North Korean nuclear weapons and fissionable materials. It is not possible to undertake both courses simultaneously.

The ultimate issue is not regional but concerns the prospects for world order, especially for a Pacific political structure along the lines of that put forward by the thoughtful Australian prime minister, Kevin Rudd. There could scarcely seem to be an issue more suited to cooperation among the Great Powers than non-proliferation, especially with regard to North Korea, a regime run by fanatics, located on the borders of China, Russia and South Korea, and within missile range of Japan. Still, the major countries have been unable to galvanize themselves into action.

In this multipolar world, many issues like nuclear proliferation, energy and climate change require a concert approach.

The major powers of the 21st century have proved to be heterogeneous and without much experience as part of a concert of powers. Connecting their purposes, however, needs to be their ultimate task if the world is to avoid the catastrophe of unchecked proliferation.

[ Related: North Korea's Nuclear Ticket to Survival | Time to Test North Korea - Nuclear Weapons | Today, North Korea; Tomorrow, Iran | Israel's Cuban Missile Crisis All the Time ]

WORLD NEWS & CURRENT EVENTS ...

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

More ASIAN CURRENT EVENTS ...

"North Korea's Nuclear Challenge"