- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

Jules Witcover

Reviving Healthcare Reform

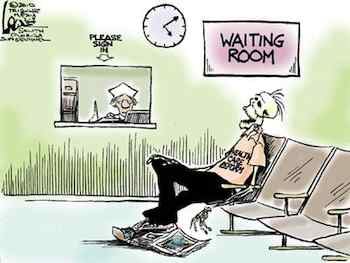

One way to look at President Obama's late personal push for health-care reform is as that of a drowning man grasping at straws, as he offers a few more concessions to congressional Republicans on the shore, who continue to thumb their noses at him.

That is the reading that could be made from his East Room final plea for bipartisanship, wherein he listed a few specific items for negotiations culled from the previous week's summit meeting on the issue. Obama endorsed "state grants on medical malpractice reform, and curbing waste, fraud and abuse in the health-care system," both pet Republican pitches.

But if the events of the last days somehow bring about the enactment of the reform legislation Obama seeks, they more likely will be viewed as the culmination of a crafty campaign to rejuvenate his presidency and his image as a political leader.

First, he will have rescued a seemingly lost cause after the Democrats surrendered their super-majority in the

To finally pass the revised Democratic health-care reform package will still require navigating a treacherous thicket through the two houses of

But Obama, in his carefully staged East Room presentation with all manner of medical personnel as live props, effectively disposed of the Republican leaders' central pitch to discard all that has gone before and "start over."

Rather than just walking away and accepting defeat on health-care reform, as many thought likely after Obama was deprived of his super-majority vote in the

In doing so, he is bucking many public-opinion polls indicating that most American voters, fed up with the drawn-out health care debate of the last year, just don't want the proposal denounced by Republicans as everything from a fiscal boondoggle to -- gasp! -- socialism.

But the merit of a poll is in the eye of the beholder. When their findings square with one's beliefs, they are touted as near infallible. In the view of those who disagree with them, they are impossibly flawed or skewed.

Political candidates in the face of polls unfavorable to them like to say that the only poll that counts is the one that's held on Election Day. Obama is in that camp, in that he is betting on the votes of 216 Democrats in the House and 51 Democrats in the

Many of them facing the voters in November may find it hard, in light of the polls, to conclude that voting for any health-care reform will constitute individual political good for them. To them, Obama is making an altruistic pitch to set aside concerns about their reelection for the greater good of the American people, 31 million of them still uninsured.

But also inherent in that plea is the greater good of the

In his pep talk Obama noted, "There's a fascination bordering on obsession in the media and in this town about what passing health insurance reform would mean for the next election and the one after that." He said he would "leave to others to sift through the politics." In the next days here, he can count on that happening.