- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

Kent Garber

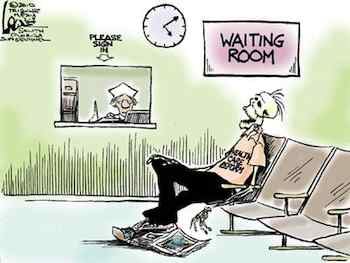

Democrats Hope Summit Will Revive Healthcare

Two Sundays ago, before the

Super Bowl, President Obama showed up on TV. He announced a "healthcare summit" on

That was one of the first official things the

The president's proposal suggests that the

Democrats know that Americans are upset about all the backroom deals that took place last year on the healthcare bills, and their hope

is that a big, open event will quiet some of those gripes about "transparency." At the same time, the

But that doesn't mean the healthcare summit can't serve a purpose.

What it could do is give Americans their clearest look so far at Republicans' ideas for changing healthcare. For all the chatter,

most of what's known about Republican ideas still comes from two places: a thin proposal filed by

The summit could clarify differences between the two parties' approaches.

One of the biggest differences is over the scope of reform.

Republicans say they want a more incremental approach, one that's cheaper and less reliant on government mandates. But that has its

limitations. As the Congressional Budget Office said last year, the

"[Republicans] don't believe as much in government," says Gary Claxton, director of the nonpartisan

Another concern is that the Republicans' preference for handling reform one step at a time could actually be more disruptive than a comprehensive, all-at-once plan. The Democrats' plan is big, experts say, in part because it has lots of safety bumpers like subsidies to help protect consumers from unexpected changes.

"If you do a lot, if you're very comprehensive, then reform itself is going to feel incremental because things move in relatively small ways," says Deborah Chollet, a senior health policy economist for the nonpartisan Mathematica Policy Research.

A piece-by-piece plan, on the other hand, has no such protections, so fixing one thing could break something else. That means that Republicans, who spent most of the past year attacking the Democrats' plan, may find themselves defending their own come late February.

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Healthcare Reform - Experts speculate about Obama's bipartisan healthcare meeting | Kent Garber