- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

By Joshua Kucera

The U.S. Cyber Challenge aims to identify 10,000 patriotic geeks and make them experts

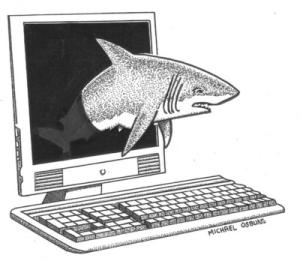

The potential threats against the United States from malicious foreign hackers are as poorly understood as they are scary. China's military has trained more than 60,000 "information troops," and its official doctrine calls for pre-emptive strikes on networks of nations it sees as a threat.

Russian hackers -- probably with Kremlin support -- have attacked Internet sites in pro-Western Estonia and Georgia. And a mysterious "worm," Conficker, infects an estimated 5 million computers around the world. Authorities don't know who controls it; cyberintelligence expert Jeffrey Carr calls it "the equivalent of a nuclear bomb" that could shut down the entire Internet.

It's the kind of shadowy, nonstate threat that the U.S. defense and intelligence bureaucracies are traditionally ill equipped to fight, but a new initiative announced last week aims to try.

A consortium of government agencies and private organizations has set up a series of competitions, called the U.S. Cyber Challenge, to

identify up to 10,000 patriotic geeks and then nurture them to become "top guns," as the Cyber Challenge organizers call them, at the Pentagon,

the

"People in the Pentagon know that the guy who looks good in a flight suit and can do 100 push-ups isn't necessarily the guy who will be

the world's best hacker," says Noah Shachtman, editor of

President Obama's announcement in May of a new cybersecurity initiative, including a cybersecurity coordinator who will report directly to the president, showed that the administration recognizes the threat from foreign hackers.

"In today's world, acts of terror can come not only from a few extremists in suicide vests but from a few keystrokes on a computer -- a weapon of mass disruption," Obama said in announcing the program.

But two months on, the coordinator has yet to be named, and there is no information about the budget the office will have. "There are still huge questions about what it's going to do," Shachtman says.

And the Cyber Challenge only highlights a huge handicap Washington faces in its fight against cyberattacks:

The hacking culture is antiestablishment, and the United States is the establishment, the

A hacker wants "to align with the underdog against the big, bad U.S., and it's going to be hard to reverse that," he says.

And there are signs the United States doesn't quite get it yet. The Cyber Challenge Web pages are laden with the kind of massive PowerPoint presentations that plague the Pentagon, "the most conventional, staid way to try to recruit innovative people," Shachtman says.

Clearly, Washington is likely to face an uphill battle.

© U.S. News & World Report