- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com: Europe

by Bruce Clark

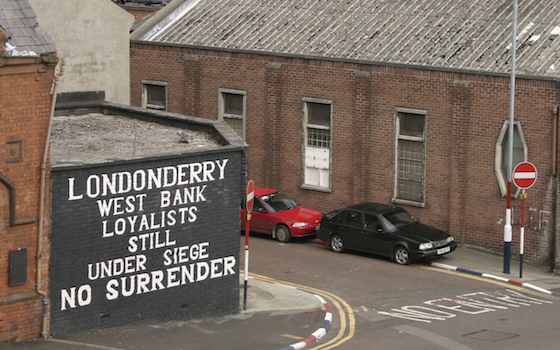

Some arresting images of the healing power of culture have emerged this year from a small city in Northern Ireland. Derry-Londonderry -- the residents argue over what to call it -- is a location where the Troubles began, a conflict that lasted a quarter of a century in which more than 3,000 people died. In

The atmosphere has lightened over the past two decades of relative peace, but it is still punctuated by small acts of violence.

People from all over the world come to walk round the magnificent city walls and visit a small museum that does a fair job of telling the story of a divided city. Visitors this year will be extra numerous because of an extended arts festival, featuring local talent and international performers.

Memorable vignettes are coming thick and fast. On the 26-acre site of a barracks which the British army abandoned 12 years ago, local guitarists played along with one of the world's masters of contemporary dance, Hofesh Shechter, who said the town reminded him of his native Jerusalem. In April, the Dalai Lama joined Catholic and Protestant clergy in walking over the Peace Bridge, a new pedestrian thoroughfare spanning the choppy waters of the River Foyle.

But not all the city's worries have been dispelled by the restorative power of the Muses. The very name of the festival, Derry-Londonderry UK City of Culture 2013, highlights the problem.

The name Londonderry dates to the town's re-foundation by English colonists in the early 17th century. Members of the city's Catholic majority, who now dominate the municipal council, long to remove the prefix London. But renaming a place established by ancient statute is not a simple business, so the hyphenated appellation is a kind of compromise. It is a peculiar paradox that the first UK City of Culture is one where most residents yearn to leave the United Kingdom. In a population of 110,000, about 75 per cent of the vote goes to nationalist parties.

The G8 summit is to be held 60 miles away in the secluded confines of the Lough Erne resort in Co Fermanagh. The political cast of the two places is similarly nationalist: It was here that Bobby Sands, an IRA detainee, was elected to the Westminster parliament while on the hunger strike that was to kill him.

The Mayor of Derry, Kevin Campbell, is a member of Sinn Fein, once the political arm of the IRA, which radically rejects the legitimacy of British rule. For now, as one prominent resident puts it, 'Sinn Fein are working the existing system'. But hardliners object, and made several minor bomb attacks on the City of Culture offices.

Meanwhile, some cultural statements are being made that reflect uncomfortable truths. A local author, Jonathan Burgess, has written a play Exodus which recalls the Protestant families who say they were forced to abandon the city's historic centre, leaving the Foyle's western bank almost entirely Catholic. City fathers say that they are keen to preserve an active Protestant role in local affairs, but guaranteeing this will require more than a walk by the Dalai Lama.

So is there something fraudulent about the implied message of Derry's cultural festival? Is it naive to imagine that excellence in the arts can both celebrate and reinforce a spirit of post-conflict reconciliation?

In the right conditions, the common language of culture -- music, film, literature, art -- can indeed be a powerful force for peace. When two groups of people have been told by their respective masters to regard one another as alien and hostile, artistic events can send a giant countervailing message.

Here are a few examples. First, a very local one: at the height of the Northern Irish Troubles, when urban spaces were segregated battle zones, young people enjoyed the same rock music. When a punk group called The Undertones emerged in the 1970s from the most battle-scarred Catholic areas of Derry, belting out witty, apolitical songs of youthful angst, they defied the masters of conflict by finding lots of fans in hard-core Protestant areas.

In the land of apartheid, something changed forever when the white American Paul Simon teamed up with black South Africans to make music which entranced the world, and then South Africa itself. Activists grumbled that he was violating a cultural boycott, but the sight of Simon appearing on stage with black singers made a more eloquent point than a thousand political tracts.

Relations between the states that went to war after communist Yugoslavia's collapse are still volatile, but nothing stops young people from Croatia or Bosnia from flocking to Exit, an electronic-music festival in the Serbian city of Novi Sad.

Take another relationship which is often seen as irreducibly hostile. Over the past 50 years of fluctuating relations between Greeks and Turks, artistic portrayals of a deep, paradoxical commonality have never ceased to resonate. Eyes watered in both countries when Dido Sotiriou, a Greek novelist, described the comradeship between two farm boys who were later divided by Greek-Turkish war. In 2003, a cult film, A Touch of Spice, used culinary images to celebrate the Greek-Turkish intermingling that persisted in Istanbul until 1964 when, amid tension over Cyprus, tens of thousands of Greeks had to leave.

What all these artistic moments have in common is that they reflected a spirit of defiance; they all involved a rejection of powerful forces which had a stake in perpetual conflict. It is a somewhat different story when reconciliation through art is fostered by officialdom. Young rock-music fans have a keen sense of when an official story is being challenged, and when it is lavishly promoted.

Magic moments in cross-cultural friendship tend to be spontaneous, not planned. For Irish music lovers across the world, the biggest show is the Fleadh (pronounced Flaah). At last year's, in Cavan, there was an electric evening when Willie Drennan, a player of 'Protestant' Ulster-Scots music connected with artists playing traditional Gaelic Irish instruments. This August the Fleadh will come to Derry; but nobody will know till then whether any such miracle of connection will recur.

Still, even if doesn't, that will not mean that Derry's cultural festival has served no honest purpose. This is a demographically young city where people under 30 are relatively untouched by conflict. Letting them enjoy and play along with the best artistic talents of a wider world can do nothing but good. A budget of £16 million goes a long way in a town of 110,000.

But some of the city's most important civic and artistic projects predate the festival and will, it is hoped, continue long afterwards. Council and business leaders want to make Derry a hub of 'digital culture' -- activities at the interface between the arts and information technology.

Digital culture makes sense for a city that has a large pool of artistic talent but is hampered by geographical isolation. Another feature of Ulster's emerging hi-tech sector is that it is free from domination by either Protestant or Catholic social networks. As a rule, the higher the tech, the less sectarianism matters; there is no such thing as Protestant or Catholic software.

Culture can douse inter-communal conflict, or sometimes inflame it. Its effects are by definition unpredictable. In the end, technology, with or without a link to the arts, may matter more.

Bruce Clark is editor of Erasmus, The Economist's religion and public policy blog, and author of 'Twice a Stranger: How Mass Expulsion Forged Modern Greece and Turkey'

WORLD | AFRICA | ASIA | EUROPE | LATIN AMERICA | MIDDLE EAST | UNITED STATES | ECONOMICS | EDUCATION | ENVIRONMENT | FOREIGN POLICY | POLITICS

Article: Copyright ©, Tribune Media Services.

"Can Culture Heal the Wounds of the Troubles?"