- MENU

- HOME

- SEARCH

- WORLD

- MAIN

- AFRICA

- ASIA

- BALKANS

- EUROPE

- LATIN AMERICA

- MIDDLE EAST

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Argentina

- Australia

- Austria

- Benelux

- Brazil

- Canada

- China

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Mexico

- New Zealand

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Poland

- Russia

- South Africa

- Spain

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- USA

- BUSINESS

- WEALTH

- STOCKS

- TECH

- HEALTH

- LIFESTYLE

- ENTERTAINMENT

- SPORTS

- RSS

- iHaveNet.com

Rob Silverblatt

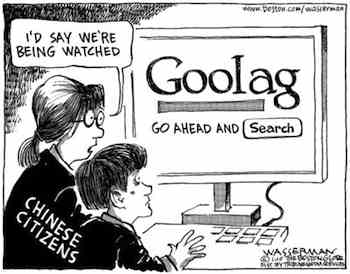

When Google moved to extricate itself from Chinese censorship laws, it set in motion what could easily have passed for a prearranged choreography.

In the opening salvo,

And right on cue, a Chinese official issued a harshly worded rebuke. "Foreign companies operating

in China must

abide by Chinese laws. Google has violated the written promise it

made on entering the Chinese market," the unnamed official said, according to state-run

Meanwhile, the Chinese government, as expected, has begun restricting access to Google.com.hk, the Hong Kong-based service to which Google began routing all Chinese users yesterday in a bid to circumvent Beijing's censorship laws.

So far, then, all has gone according to script. What will happen next is far more difficult to predict. Notably, as business relations between the United States and China sour, many see

"I think it can be seen as part of a broad deterioration in the business environment in China," says Nicholas Lardy, a senior fellow at the

But will other companies follow Google out the door? "That's the $64,000 question," Lardy says. "The pattern in the past has been the foreign firms complain--sometimes justifiably, sometimes not--whenever they see things moving in a direction that they don't like. But the number of significant firms that have ever withdrawn from the market is extremely small."

Still,

Even before

And even as Chinese officials slam Google, they are taking a conciliatory approach toward the overall theme of the country's corporate climate. "The Google incident is just an individual action taken by a business company, and I can't see its impact on China-U.S. relations unless someone wants to politicize that," Qin Gang, a spokesperson for China's

In the short run, it's unlikely that companies will mimic

Still, even if they are inclined to follow in

Another salient issue is that many U.S. companies that have offices in China are in manufacturing, meaning that they have invested substantially in machinery, warehouses, and other physical assets. "They have a lot more constraints than a technology company like Google," says Lardy.

Overall, then, it appears that most of the immediate fallout from

According to the Beijing-based research firm

At the same time, though, Oberweis says that if Baidu gains a stranglehold on China's Internet search market, users could be put off. "Clearly, Internet growth in China is on a tear right now, and irrespective of this situation, I think it will continue to grow," he says. "But it might grow a little bit less quickly if Baidu, with strong government influence, is the experience that Chinese consumers are forced to [accept]."